Troubling Trends

It’s 6PM in Syracuse: the traditional ballet of good and bad news can begin. A local teller got robbed, international tensions reach new highs. A lucky lottery winner took home an obscene amount of money, while the EU was enacting new data protection laws.

Like most people, we respond strongly to relatable issues, even more so when delivered by familiar and trusted voices. In this sense, local news really is the bedrock of most people’s information stream, despite the rise of social media. As you walk into a friend or family’s home, chances are the television will be on. A familiar face on screen, and in the corner a familiar logo, staples of American TV journalism over the last half-century: ABC, CNN, Fox News, CBS, MSNBC …

“Hi, I’m [name] with [station]. Our greatest responsibility is to serve our communities. I am extremely proud of the quality, balanced journalism that [station] produces, but I’m concerned about the troubling trend of irresponsible, one-sided news stories plaguing our country.”

Now, this is curious. Tuned into your local station, you listen on as the journalists proceed to recite a tirade about the importance of impartiality in journalism 1, name-dropping the most popular “fake” of the year. Yeah, you’ve heard this before. Even the President is tweeting furiously about it 2.

The Fake News Networks, those that knowingly have a sick and biased AGENDA, are worried about the competition and quality of Sinclair Broadcast. The “Fakers” at CNN, NBC, ABC & CBS have done so much dishonest reporting that they should only be allowed to get awards for fiction!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 3, 2018

As it turns out, your local station is not the only one to have run this segment. Across the country, news anchors recite variations of this text, warning against “some members of the media [that] use their platforms to push their own personal bias and agenda to control exactly what people think”. This message was aired, often more than once, across the country: CBS 12 in West Palm Beach, Florida, NBC 16 in Eugene, Oregon, Fox 28 in Columbus, Ohio, … 3

Why would all these local stations, apparently across affiliations, decide to coordinate a full-on attack on mainstream media? It turns out they didn’t choose to, the institution that owns their station did, and some anchors were furious about it 4.

“We hated the way the PSA bashed other news outlets and the way it insinuated that we were the only truthful news source — despite the rightward tilt our network has taken over the years. Our anchors privately said they felt like corporate mouthpieces, especially when they found out no edits of the script were permitted. Yet bosses made it clear that reading the message wasn’t a suggestion but an order from above.”

Extract from an op-ed published in Vox by Sinclair Journalists 4

Many of these stations are not actually operated by their namesakes: they essentially act as franchises. The largest local news operator in the country is called Sinclair Broadcasting Group, which owns close to 200 local stations in the United States. This number could even be extended if the $3.9 billion merger with Tribune Media 5 comes through. It is currently under review by the FCC, under the suspicion that it would effectively create a monopoly. While antitrust laws and broadcasting policies could block the transaction, the new administration seems keen on loosening the leash, with FCC chairman Ajit Pai already moving to dismiss some of these regulations 6.

Sinclair, the author of this anti-fake news manifesto, has also come under fire over the years for this very behaviour of pushing stories to its affiliates, compromising their journalistic independence. In 2004, they broadcasted an anti-Kerry documentary 7 nationwide, ever since raising questions 8 about the conservative slant 9 of their stations’ reporting 10. Recent reports have stated that there is mandatory material for Sinclair-owned stations, including pro-Trump commentary by his former aide Boris Epshteyn and a security threat segment called ‘Terrorism Alert Desk’, turned to ridicule by HBO’s John Oliver in an episode dedicated to the company11.

To quote the memo directly: “This is extremely dangerous to our democracy”.

Finding Patterns

When broadcast syndications were first envisioned, they answered a very real need to reduce costs for local stations. Pooling resources between small news organizations was the most sensible way to provide journalists with more time for local news while providing a view of the world’s events.

Given the fractal scale at which the world’s events occur, editors must make decisions with respect to the type of information they will send downstream. Informed by geographic considerations, editorial guidelines, thematic regards or even logistic capabilities, this filtering process is very likely to introduce an imbalance in the stories that editors choose to promote. Some events will end up over- or under-represented, which introduces a selection bias. When larger organizations, such as Sinclair, push information downstream to their affiliates, the decision process becomes even more visible thanks to the scale at which it skews the event space.

An interesting way to uncover these biases is to look at the interaction between sources and events: who covered what? Without any regard for the content of what was covered, the interactions alone are useful to extract some idea of source’s preferences. Studying this information is actually a common setting in a field of machine learning called collaborative filtering. For example, without even knowing what your preferred genre or who your favorite actor is, it’s likely that you will want to watch a movie that people who like similar movies to yourself also liked. The same idea can apply to news coverage: a given source’s coverage could be inferred from sources similar to itself.

These methods have recently come under fire, with people accusing companies like Facebook of leveraging personalisation techniques to bias people’s decision making process. However, by realising that a decision process is a preference process, the same technology can be leveraged to de-bias news channels. This is what is proposed in our paper, “Selection Bias in News Coverage: Learning it, Fighting it” (WWW’18)12.

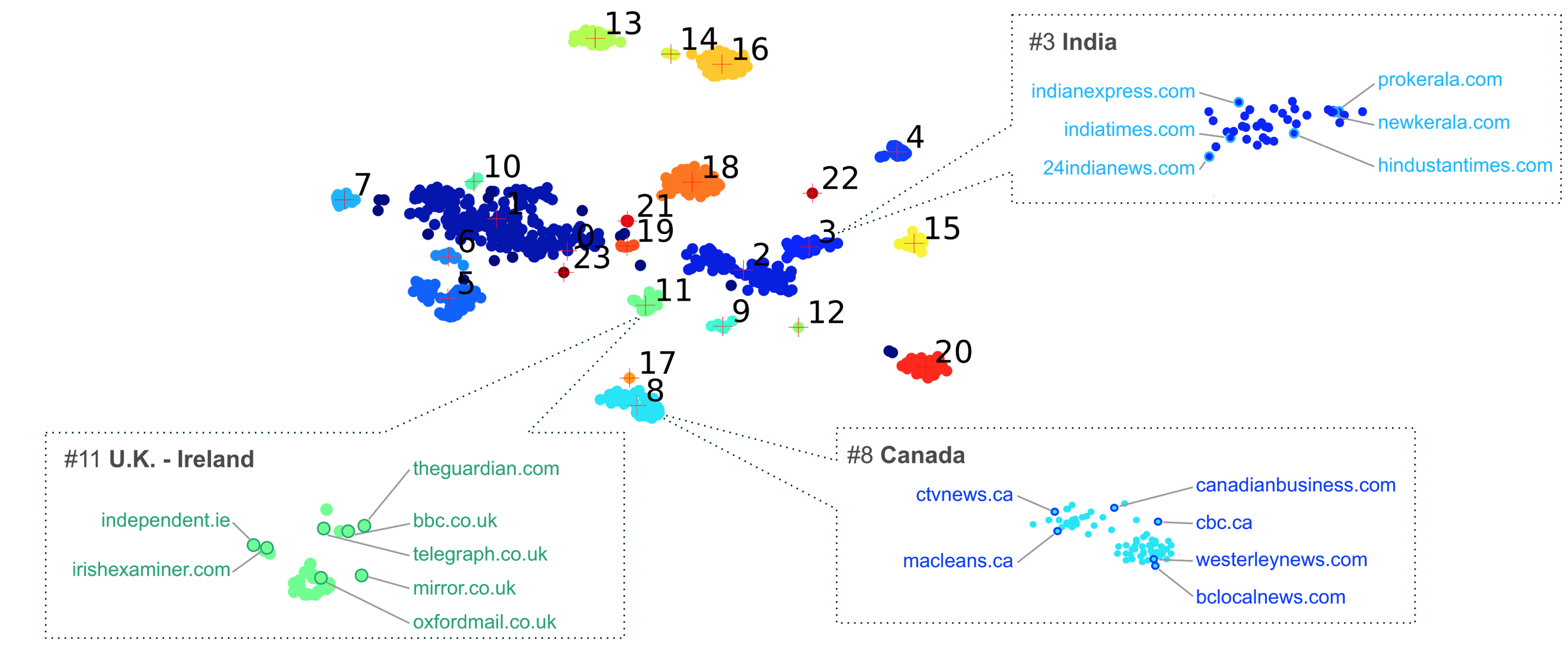

Following this insight, the first bias that we identify is an obvious one: geographically related sources have a tendency to cover similar events. This is reassuring in the sense that local news is actually doing what it was meant to do in the first place: community-centric reporting.

Figure 1: Geographical clusters in the selection space (Click here for an interactive version12)

Interestingly though, a second type of cluster emerged. The first time we started sifting through the algorithm’s results, we figured there must be something wrong. What does Fox 25 in Oklahoma City have to do with ABC 20 in Springfield, Illinois 3? After scrolling through dozens of these websites, a pattern started emerging: similar website themes, as if they were all using the same template, and at the very bottom of the page, the mention of a common “Broadcasting Group”.

Figure 2: Subtle footer structure

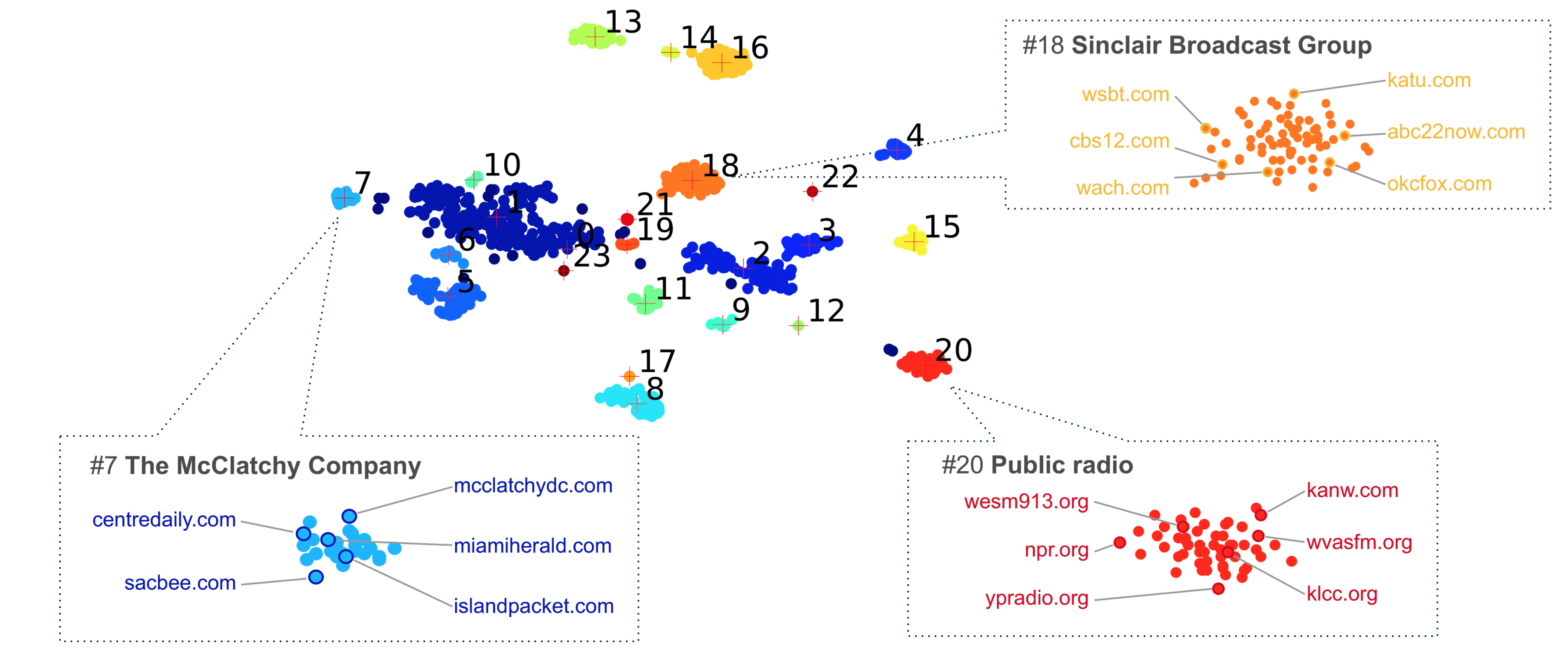

Our method did what it was intended to do: we identify and bring together sources with similar decision processes. The clusters we identify are non-obvious, especially without access to the content, and most don’t even have the same branding since they are often franchised outlets.

Figure 3: Broadcast syndication clusters in the selection space (Click here for an interactive version12)

While certainly not exhaustive, our method was able to detect and group local stations that were all part of larger structures, such as Sinclair Broadcasting Group, which controlled swaths of news outlets across the country.

Using Similarities to Diversify

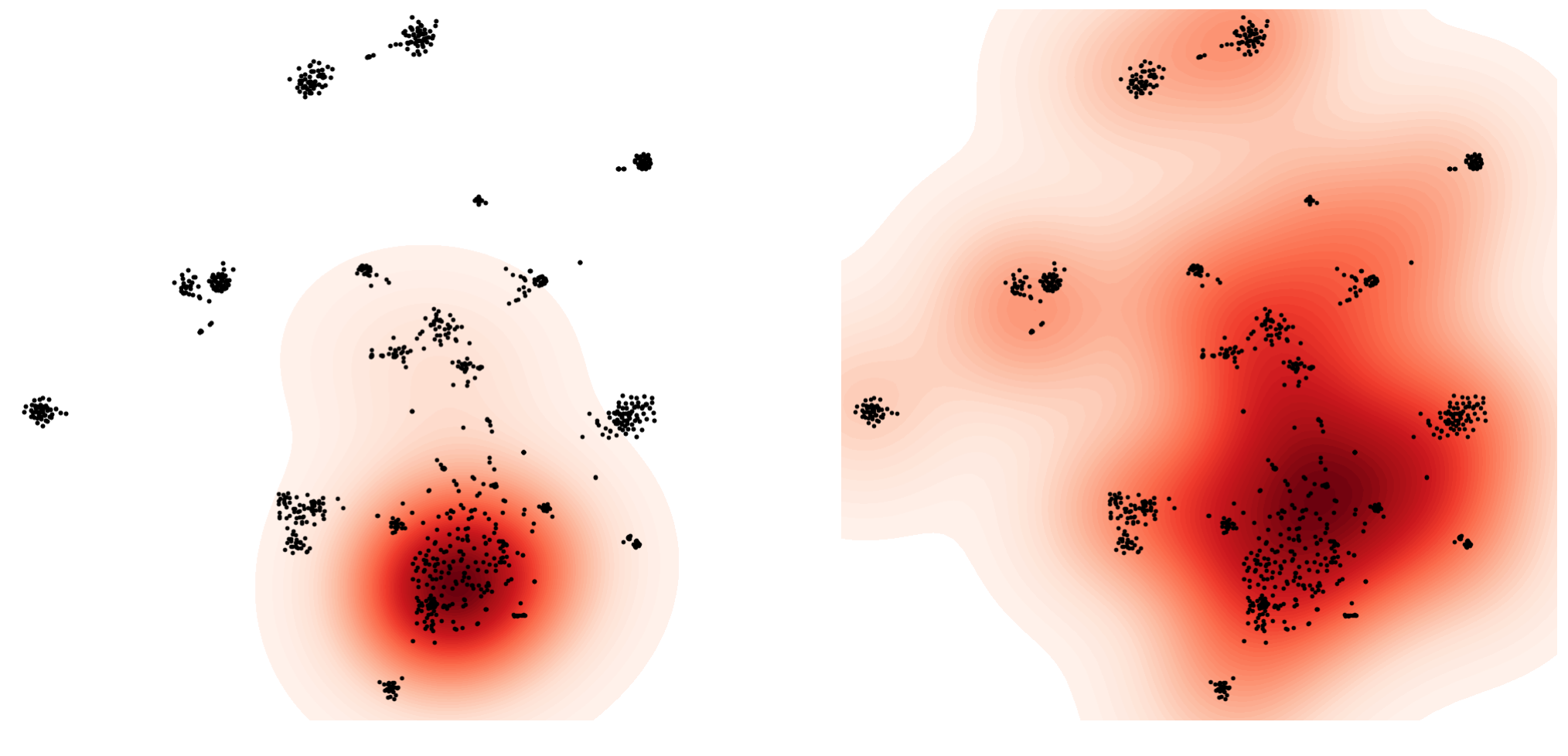

Take the case of a news aggregator for example, who must select a set of sources from which to broadcast information. The simple method would be to select the sources that cover the most events, since you would assure that most events would be shown to your readers. Unfortunately we show that while the number of articles is high, the number of actual events these articles refer to is quite low. Additionally these sources are shown to be very similar in the selection space (Fig. 4, left). In other words, there is a lack of diversity in the news coverage.

In our paper, we propose to leverage our new measure of similarity between news sources. If we were to select sources to display our users, we could use this similarity to ensure that the chosen subset is one that you would enjoy, similar to the source you are currently reading. This is the setting in which most recommendations operate, trying to batch similar things together to group consumption. In the instance of social networks or news, this leads to a filter-bubble or echo-chamber effect, where the same information is stuck in a bubble of like-minded news conveyors. Instead, we could decide to leverage this similarity to do the opposite: choose sources as different from each other as possible (Fig. 4, right). This could be a nice way for our example news aggregator to propose a diversified coverage to its audience.

Figure 4: A selection of Popular sources (left) vs a selection of Diverse sources (right) in the selection space

Of course, this cannot be considered a solution to “fake news”, and one should be weary of such claims of technology as the universal problem solver. Nevertheless, the use of popular machine learning methods has yielded interesting insights into the way streams of information are fed. This opens the door for media accountability frameworks which use the only thing that no media outlet can hide: the content that they cover.

It already seems inevitable that news curators take over the role of filtering the news for us, as many people already get their news through curated channels such as Facebook 13 or Naver 14. This work is unfortunately just an attempt at mitigating some of the effects of these curated platforms. News connected the world before instantaneous sharing, allowing people to share the events of their communities across the globe. While it is unrealistic to believe that we can keep up with the immense body of information being produced across the world, we must realize the importance of a free, diverse and levelled press, and the threat the lack of these values represents to our perception of the world around us.

Notice

If you are interested in our work, have questions about the study or would like to share this article, feel free to contact me at any of the channels listed above or on my website. The paper is licensed under a CC-BY (4.0) license, as are the figures included in this article.

Edits

- Monday, April 30th: Added a couple paragraphs to clarify some aspects such as the need for curation and potential applications, thanks to comments from reddit (/r/journalism) and the relationship to personalisation, thanks to Romain Pittet

Bibliography

-

List of Sinclair operated stations, by affiliation link ↩ ↩2

-

“We’re journalists at a Sinclair news station. We’re pissed.”, Anonymous (published on Vox) link ↩ ↩2

-

Sinclair Broadcast Group: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO) video ↩

-

Selection Bias in News Coverage: Learning it, Fighting it, WWW’18, D. Bourgeois, J. Rappaz, K. Aberer link ↩ ↩2 ↩3