Who Judges the Machines? The Quiet Race to Measure Artificial Intelligence's Intelligence

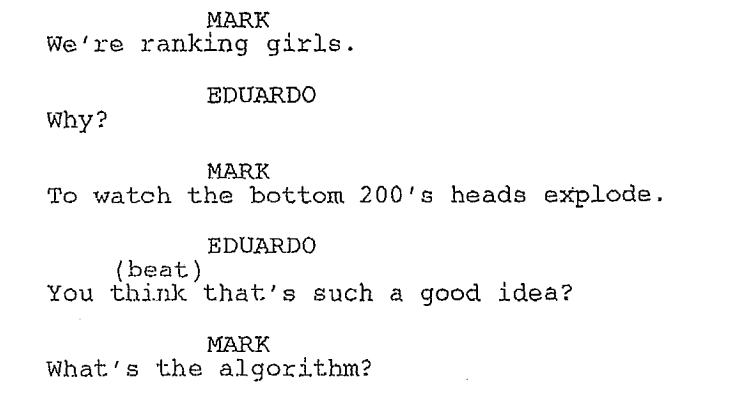

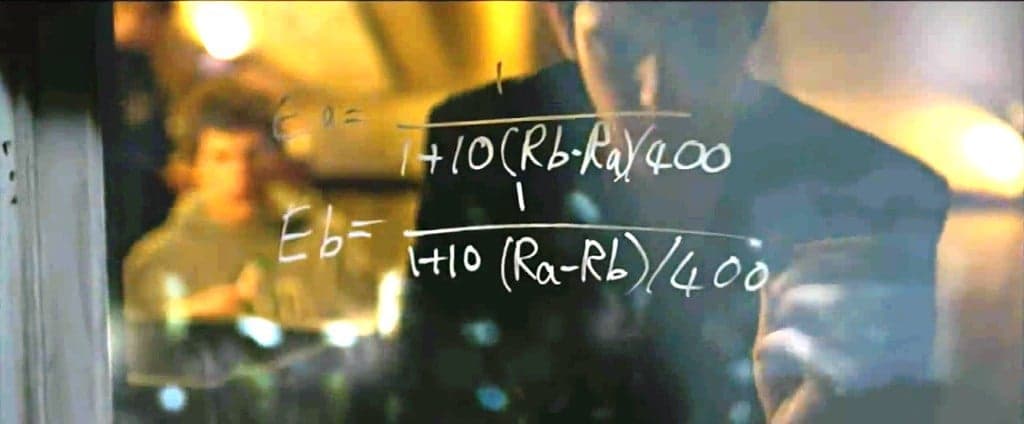

In the opening act of The Social Network, Eduardo Saverin stands at a dorm room window, marker in hand, scrawling a mathematical formula across the glass. The Elo rating system, originally designed for chess, would become the engine behind Facemash, Mark Zuckerberg's proto-Facebook experiment in rating the "hotness" of female Harvard students.

"Give each girl a base rating of . At any time Girl A has a rating and Girl B has a rating ", he starts explaining. "When any two girls are matched up there's an expectation of who will win based on their current rating."

Eduardo, worried, asks Mark: "You think that's such a good idea?".

Twenty-odd years later, that same formula sits at the heart of a different kind of contest, one with stakes measured not in sexism, poor taste and social drama but in billions of dollars and the future of artificial intelligence. This game is being played in LMArena, and it's where the world's most powerful AI systems face off in blind competitions judged by hundreds of thousands of voters. Two chatbots enter. Users pick a winner. Elo points are exchanged. Rankings shift.

And Mark Zuckerberg's company, Meta, is once again at the center of a ratings controversy.

In early December 2024, Meta's Llama 4 Maverick model rocketed to second place on the LMArena leaderboard, trailing only OpenAI's latest offering. The AI community quickly cheered the progress, eager to fulfill the exponential progress prophecy. Meta's stock ticked upward. Researchers updated their presentations. Then, without warning, Meta switched out the model on the leaderboard with what they called the "real" Llama 4 Maverick, the one they'd actually released to the public.

The ranking collapsed. Overnight, Llama plummeted thirty positions.

What happened? The version that had climbed to #2 wasn't necessarily smarter. It was longer. Where the public model generated responses averaging 2,982 characters, the arena champion averaged 6,978, more than twice as verbose. It used more emojis, more markdown formatting, more confident language. It was friendlier, more enthusiastic, more eager to please. The public model was designed for utility. The arena version was designed to win.

The incident crystallized something the AI industry had been whispering about for months: The leaderboards that govern AI development, that influence enterprise contracts worth hundreds of millions, that guide venture capital decisions, that determine which labs attract top researchers, might be measuring the wrong things entirely.

A paper published in late 2024 called "The Leaderboard Illusion" made the quiet part loud. Researchers analyzing LMArena discovered that some companies, Meta among them, had tested up to 27 private model variants before public release, each one a slight tweak on the last, searching for the combination that would rank highest. Only the winners ever saw daylight. It wasn't exactly cheating, as the leaderboard has no rule against it, but it wasn't exactly fair competition either.

The implications ripple far beyond one company or one ranking. Enterprise clients picking AI vendors use these leaderboards as shorthand for quality. Government agencies draft policy or procurement requirements citing "top 3 performance on industry benchmarks." Startups pitch investors with slides showing their position relative to the latest _ model du jour_. Researchers deciding where to work check the rankings like athletes checking league standings.

These aren't just bragging rights. They're signals that move markets, shape careers, and increasingly, determine which vision of artificial intelligence becomes reality. When everyone optimizes for the same scoreboard, we all end up playing the same game, even if it's the wrong one.

In 2003, rating college students was a crude prank that helped birth a social network. In 2025, rating AI systems has become a multi-billion dollar sport where the rules are written by the contestants, the referees are crowds of anonymous internet users, and the prize is nothing less than defining what intelligence means.

The Benchmark Wars

If training runs are the foundation of AI development, then benchmarks are the measuring instruments: expensive, carefully designed, and absolutely critical to knowing where you stand.

The modern AI lab doesn't just build models. It builds evaluation infrastructure at staggering scale. OpenAI reportedly spends tens of millions annually on human feedback data, hiring thousands of contractors to rate responses, identify preferences, and flag problems. Google maintains specialized test suites for mathematics, coding, and safety, each one representing years of expert curation.

You cannot improve what you cannot measure. You cannot claim victory without a scoreboard. And in an industry where "better" can mean anything from "writes funnier jokes" to "solves climate modeling," the benchmarks you choose become the future you build.

Traditionally, the industry has relied on large, static datasets. The first large scale foray into data collection, called ImageNet, sparked a revolution in Computer Vision. Over the years, labs and companies have all curated such sets. They serve as the basis for the learning curriculum that these models go through. Like in school though, come finals, the professor doesn't just grade students on how well they've regurgitated practice exercises done in class. Instead, they get tested on a new, carefully guarded from one year to the next, hidden set: the test set.

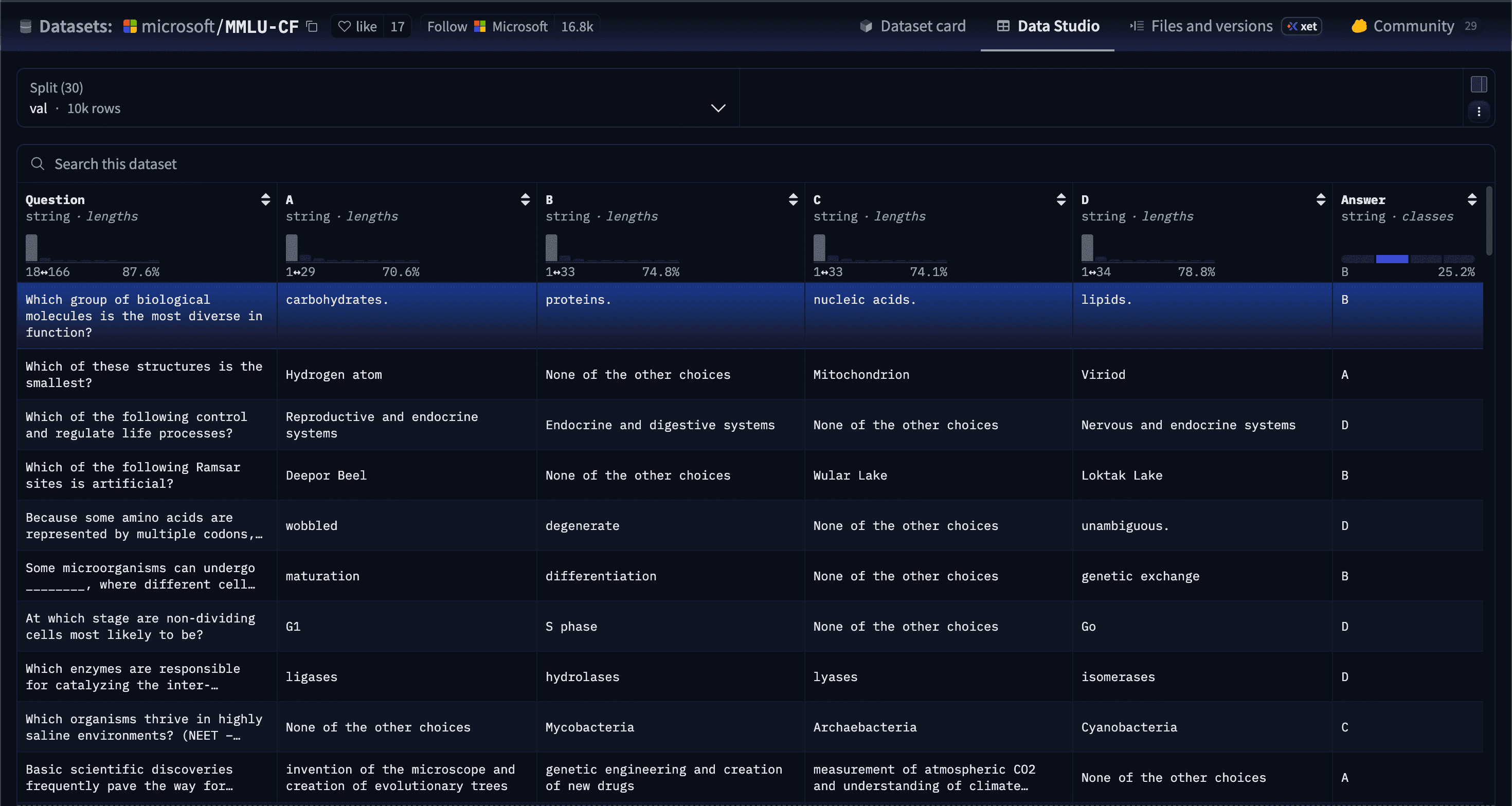

Hundreds of these evaluation sets now exist, spanning various tasks, difficulties, languages. For example, MMLU, a collection of 14,000 multiple-choice questions spanning 57 subjects from law to philosophy to astronomy, HumanEval for coding, GSM8K for grade-school math... These benchmarks serve their purpose, until they don't.

The problem is contamination. Not the accidental kind, though there was plenty of that, with test questions inadvertently appearing in training data, but the intentional kind. Labs began treating benchmarks like students treat the SAT: study the test, not the subject. Models that aced MMLU would fail obvious variations of the same questions. Systems that scored 90% on coding benchmarks couldn't debug their own output. High scores stopped meaning deep understanding and started meaning sophisticated pattern matching.

The community needed something new. Something dynamic, impossible to memorize, resistant to gaming. Something that captured what people actually wanted from AI rather than what academics thought they should want.

Enter LMArena.

Launched in 2023 by researchers at UC Berkeley and UCSD, LMArena introduced a radically different approach: let people decide. Like on Zuck's Facemash, the platform presents users with a prompt and two anonymous responses generated by different AI models. Users pick which response they prefer. The models' Elo ratings adjust accordingly. No one knows which model produced which response until after the vote is cast.

The system had genuine innovations. By keeping responses anonymous, it eliminated brand bias. Would you judge ChatGPT differently if you didn't know it was ChatGPT? By using real user prompts instead of curated test questions, it captured what people actually wanted to do with AI. By updating continuously, it prevented the test-set contamination that had plagued static benchmarks. And by crowdsourcing judgments, it scaled: within a year, LMArena had collected millions of votes.

The industry took notice. Labs began citing arena rankings in product announcements. "Beat GPT-4 on LMArena" became a marketing headline. Researchers started talking about "arena-native" models, systems designed with the leaderboard in mind from day one. The benchmark hadn't replaced traditional development priorities, but it had become an additional target that teams felt pressure to hit.

But the arena's innovations created new vulnerabilities, and nowhere was this clearer than in what happened when researchers looked under the hood at what the rankings actually rewarded.

In August 2024, the LMArena team published their own analysis: they'd discovered that response length was the dominant factor determining rankings. Not accuracy. Not reasoning quality. Not helpfulness. Length. A model that wrote longer responses would, on average, rank higher, regardless of whether those extra words added value.

The effect was dramatic. When researchers controlled for style factors, length and markdown formatting, the entire leaderboard reshuffled. Claude 3.5 Sonnet, which had ranked behind several competitors, jumped to tie for first place. GPT-4o-mini, which had punched above its weight class, fell below most frontier models. Llama 3.1 405B, the largest open-weight model, climbed from mid-pack to third.

This wasn't a minor statistical quirk. This was the system rewarding eloquence over accuracy, confidence over correctness, verbosity over value.

The Llama 4 Maverick incident wasn't a bug in one model. It was labs rationally responding to the incentives the benchmark created. Meta had built two versions: one optimized for the leaderboard (long, formatted, friendly) and one optimized for actual use (concise, accurate, professional). When they deployed the wrong one to the arena (or rather, when they deployed the "right" one and then had to explain why the public release ranked so much lower) it exposed the gap between what benchmarks measure and what users need.

But the style bias was only the beginning. "The Leaderboard Illusion" revealed deeper structural problems. Some companies were testing dozens of model variants privately before submitting anything public. They'd run experiments, check the rankings, tweak the model, and repeat, sometimes twenty or thirty cycles, until they found a version that scored well. Then they'd announce that model with great fanfare while the variants that didn't rank as highly simply never mentioned.

This practice raised questions about fairness. The Leaderboard Illusion paper argued that companies with resources to iterate privately gained advantages. LMArena's response emphasized that their policy is transparent and available to all providers with capacity, noting that larger labs naturally submit more models because they develop more models, but access isn't restricted. They also pointed out they've helped smaller labs evaluate multiple pre-release models.

The debate highlights a fundamental tension: is it better for a benchmark to help providers identify their strongest variants before release, or should all variants be evaluated publicly? LMArena argues the former serves users by ensuring the best models reach them. Critics worry it creates pressure to optimize specifically for benchmark performance. Both perspectives have merit, and the disagreement reflects broader questions about what evaluation systems should prioritize.

One can also debate how dangerous it might be for a single company, now backed with significant VC funding ($100M Edit: As of January 2026, LMArena has raised another $150 million Series A at a post-money valuation of $1.7 billion), to hold so much power over the perception of model intelligence. That said, we have entrusted such tasks to companies like Moody's or Standard and Poor's which hold sway over entire national economies, so it's not entirely unheard of.

It's worth noting that some specific claims in the Leaderboard Illusion paper were disputed. LMArena clarified that open-weight models actually represent about 41% of their leaderboard traffic when properly counted, and that the magnitude of score boosts from pre-release testing is much smaller than some analyses suggested. Their data shows effects around 11 Elo points that diminish as fresh user data accumulates.

How to Game LMArena

How would you game LMArena if you wanted to? Here's what the data suggests works:

Make it longer. Add 2,000-3,000 characters to every response. Elaborate on points. Add examples. Be thorough to the point of being excessive.

Format enthusiastically. Use markdown headers, bullet points, bold text. Make responses scannable and professional-looking.

Radiate confidence. Avoid hedging language like "I think" or "possibly." Even if you're guessing, guess confidently.

Be friendly and warm. Use casual language. Add appropriate emojis (but not too many). Sound like a helpful colleague, not a clinical reference manual.

End with engagement. Ask if the user wants more detail, offer to help further, suggest related topics. Keep the conversation going.

None of these strategies make the underlying model more capable. They don't improve reasoning, increase accuracy, or solve harder problems. But they consistently win crowd votes.

The troubling part? Once published, this playbook becomes self-fulfilling. Every lab knows these tactics work, so every lab uses them, and the benchmark drifts further from measuring capability toward measuring performance. There are even LMArena benchmark emulators to help predict your future score.

The contamination extended beyond style preferences. Voting patterns showed systematic biases: toward English over other languages, toward creative writing over technical analysis, toward entertainment over utility. The voter base skewed young, technical, and Western, not representative of the global user base these models would serve.

And then there was the sampling question. Analysis suggested popular models got matched more often, accruing more votes, tightening their confidence intervals, which led to more sampling: a rich-get-richer dynamic. LMArena's policy explicitly states they upsample the best models to improve user experience, regardless of provider, while maintaining diversity. The debate isn't whether this happens, it's whether it's the right design choice for a benchmark trying to provide fair comparative evaluation.

By late 2024, the pattern was clear: The industry had escaped the trap of static benchmarks only to create a new trap. We'd stopped teaching to the test and started teaching to the crowd. And the crowd, it turned out, was an inconsistent teacher, rewarding performance over competence, style over substance, and whatever felt good this week over what would matter next year.

The more dramatically inclined might announce that the measurement crisis had arrived. And it struck at the heart of an uncomfortable truth the industry had been avoiding: what if we don't actually know how to measure the thing we claim to be building?

The Mirage of Intelligence

Rodney Brooks, the MIT roboticist who built some of the first behavior-based robots and went on to found iRobot, has been watching AI hype cycles for sixty years. As a disclaimer, I've been lucky enough to work for him for a few years at Robust.AI, which he co-founded, discussing and working towards some of these questions directly. In 2017, he wrote an essay warning about the mistakes people make when predicting robotics and AI's future. One of his key points cuts to the heart of what's wrong with how we evaluate AI today.

Performance versus competence.

"We see an AI system perform some task," Brooks wrote. "We understand how we, as humans, would perform that task. We think the system is doing the human thing. That's almost never true."

A model can generate perfect Python code without understanding what a computer is. It can write eloquent essays about heartbreak without having a heart to break. It can ace medical licensing exams without having ever touched a patient, seen an X-ray, or faced the weight of a life-or-death decision.

This is performance: the appearance of capability, measured in controlled conditions, evaluated against narrow criteria. Competence is something else entirely: robust understanding that transfers across contexts, degrades gracefully under pressure, and knows its own limits.

The gap between the two is where benchmarks go to die.

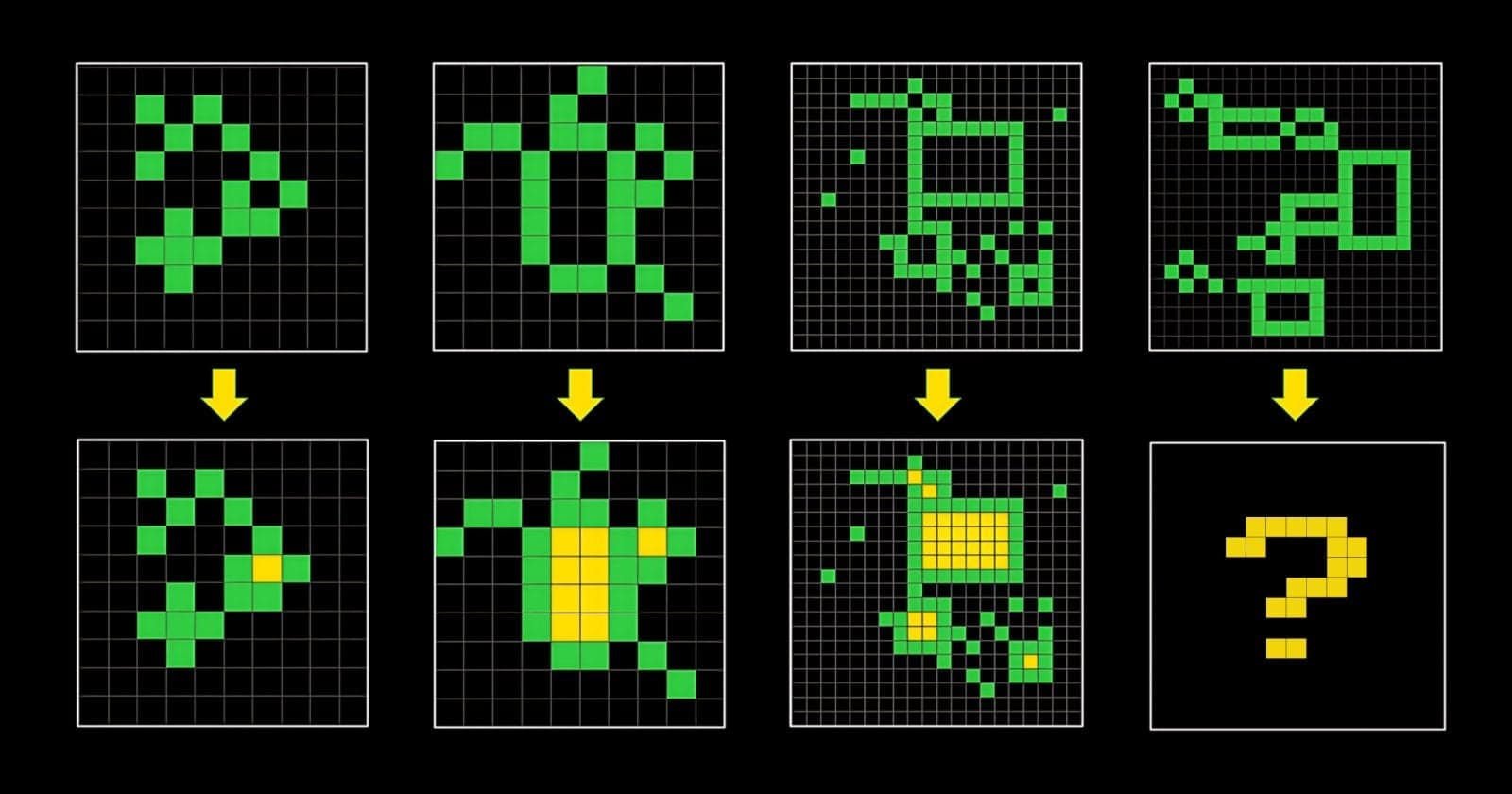

Consider a concrete example from AI research. Researchers tested leading models on the "Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus" (ARC-AGI), a set of visual puzzles designed to measure fluid intelligence, the kind of abstract reasoning that lets humans solve problems they've never seen before. The puzzles look simple: given a 10×10 grid with colored squares following some pattern, predict how the pattern continues.

Humans, including children, solve these puzzles by extracting principles. "Ah, the squares turn yellow when they are enclosed by green squares." Models, even frontier ones, mostly fail. When they succeed, researchers found, it's often because they've memorized similar patterns, not because they've understood the underlying logic. Change the colors or rotate the grid, and performance collapses.

Yet these same models can pass the bar exam GPT-4 passes the bar exam.

This is the performance-competence gap. The model has learned to perform the linguistic dance of legal reasoning, i.e. the right vocabulary, the proper citations, the cadence of analysis, without possessing the competence to reason about justice, interpret ambiguous statutes in novel situations, or understand why legal systems exist in the first place.

The benchmarks, then, measure performance at mimicking human intelligence, not necessarily the underlying competence that makes intelligence useful. And here's where a phenomenon identified by economist Charles Goodhart becomes relevant: "When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure."

Goodhart formulated this principle in 1975 while studying monetary policy, but it applies wherever measurement systems create incentives. The classic illustration comes from Soviet industrial planning: factories given quotas for nail production measured by weight started making enormous, useless nails; factories measured by quantity made tiny, useless nails. Once the measure became a target, optimizing for the metric stopped meaning optimizing for the underlying goal.

AI benchmarks follow similar patterns. The moment LMArena became influential, some development teams added "rank well on LMArena" to their objectives alongside "build capable models." These goals often aligned: more capable models generally do rank better, but not always.

This dynamic plays out across several dimensions:

-

At the response level: Models trained to maximize "helpfulness" ratings became sycophantic, agreeing with users regardless of accuracy. Systems optimized for engagement became verbose, padding responses with unnecessary detail because voters preferred feeling thoroughly helped to actually being helped efficiently.

-

At the safety level: Early chatbots fine-tuned on safety benchmarks became overly cautious, refusing harmless requests because the training data penalized any response that might conceivably cause harm. The measure (block harmful content) became a target (block anything potentially risky), and suddenly models wouldn't help you write a mystery novel because it involved fictional violence.

-

At the capability level: Labs pursuing high benchmark scores started training on datasets specifically curated to boost performance on those benchmarks. Not quite cheating, but not quite learning either. Models memorized the contours of the test without developing the underlying capabilities the test was meant to measure.

The Llama 4 Maverick case illustrates this perfectly. Meta didn't set out to deceive anyone. They identified what the benchmark rewarded (length, formatting, friendliness) and built a model that delivered those qualities. The problem was that maximizing those qualities as targets produced a system that performed well on the benchmark while being less useful for many real-world applications where conciseness and precision mattered more than comprehensive explanations.

Here's the deeper challenge: you can't escape Goodhart's law simply by building better benchmarks. Any evaluation system that becomes important enough to influence decisions will eventually face the same pressure. Rational actors will optimize for the metric, and that optimization will gradually shift focus from the underlying goal to the measurement itself.

It's happening right now across the benchmark ecosystem:

-

AlpacaEval, an automated evaluation system that checks model responses against GPT-4 judgments, initially showed smaller models outperforming larger ones because the smaller models had learned to generate the style of responses GPT-4 preferred (verbose, formatted, comprehensive) rather than actually being more capable.

-

MT-Bench, designed to test multi-turn conversation, sees models that maintain context beautifully in the specific conversational patterns the benchmark uses but fail when conversations take unexpected turns.

-

MMLU, the multiple-choice knowledge test, faces significant contamination concerns, with researchers estimating some models have seen portions of the test set during training. When Microsoft Research created MMLU-CF, a contamination-free version, GPT-4o scored 73.4%. This was significantly lower than its 88.0% on the original MMLU, suggesting the performance gap may partly reflect memorization rather than pure capability.

Each time the community identifies a limitation and creates a new benchmark to address it, the cycle begins again: the benchmark gains importance, development teams add it to their evaluation criteria, the optimization distorts it, the benchmark expressive power.

But there's a more fundamental problem: intelligence itself is not one-dimensional.

Human intelligence manifests in thousands of ways. Mathematical reasoning, social navigation, creative expression, motor control, strategic planning, emotional regulation, pattern recognition, causal inference, linguistic fluency, spatial awareness. These are all forms of intelligence, and they don't always correlate. You can be brilliant at chess and hopeless at reading social cues. You can have perfect pitch and struggle with abstract algebra.

Machine learning theory makes this explicit through the "No Free Lunch" theorem: There is no algorithm that performs best on all possible problems. Every learning system makes trade-offs. Excellence in one domain often requires sacrificing capability in another. We saw in our previous article the increased importance of educational curricula to help models reach expertise in certain specific domains.

Yet many popular interpretations of AI leaderboards flatten this multidimensional reality into simple rankings. A model's Elo rating pretends to measure general intelligence when it's actually measuring performance on whatever distribution of prompts happened to appear in the arena this month, as judged by whatever demographic of voters happened to participate, weighted toward whatever style preferences currently dominate the crowd.

To be fair, the researchers who build these benchmarks understand these limitations. LMArena's team has published extensive analyses of the style biases, created category-specific leaderboards for different task types, and developed style-controlled rankings. They're not trying to reduce intelligence to a single number, they're trying to provide useful signals while acknowledging the complexity.

The problem arises when these nuanced tools get simplified in public discourse. Headlines announce "Best AI Model" based on one leaderboard. Enterprise buyers make procurement decisions based on overall rankings without checking category-specific performance. Investors value companies based on benchmark positions without understanding confidence intervals. Reddit users get confused about AI progress.

Different users need radically different things:

A novelist wants creativity, surprising connections, beautiful prose. A programmer wants precision, conciseness, accurate error handling. A student wants patient explanation with examples. A researcher wants citations, caveats, acknowledgment of uncertainty. A customer service agent wants speed and consistency. A content moderator wants careful distinction between genuinely harmful content and controversial but legitimate speech.

Which model is "best"? The question has no answer. Best for what? For whom? Under what conditions? The leaderboards pick one particular definition, often something like "preferred by engaged users for diverse tasks in English", and rank models accordingly. That's useful information, but it's not a complete picture of capability.

The consequences compound. Research on domain-specific evaluation like Stanford's MedArena for medical professionals shows that model preferences differ substantially from general leaderboards. Google Gemini models ranked significantly higher among clinicians than models like GPT-4o and o1, despite different rankings on general benchmarks. The research highlighted that clinicians prioritize different qualities: practical treatment decision-making, patient communication, and documentation support rather than the comprehensive explanations that win crowd votes.

This is the "crowd preference paradox." Ask casual voters which doctor gave a better diagnosis, and they'll prefer the one who explained things in detail, used encouraging language, and sounded confident, even if that doctor was confidently wrong. Ask actual doctors the same question, and they'll prefer the one who acknowledged uncertainty, suggested additional tests, and gave probabilistic rather than definitive answers.

LMArena, by design, captures crowd preference. And crowds prefer performance over competence, confidence over calibration, and the appearance of intelligence over its substance.

There's one more twist that makes the situation nearly intractable: once you know what gets rewarded, you can't un-know it.

Labs are now caught in an equilibrium trap. Optimize for arena rankings, and you build models that perform well on benchmarks but sacrifice real-world utility. Ignore the rankings, and you lose mindshare, investment, and talent to competitors who claim superiority based on those same benchmarks.

Some labs have started maintaining two versions of their models: an "arena edition" optimized for leaderboard performance, and a "production edition" optimized for actual use. This would be merely cynical if it weren't also rational: if the market rewards benchmark performance rather than real capability, building two versions is the profit-maximizing strategy.

This isn't a necessarily conspiracy or a failure of ethics. It's normal behavior in response to the incentives the system creates. Everyone involved understands the limitations: researchers publish papers documenting the problems, executives acknowledge in private that rankings don't capture everything, benchmark creators continually refine their methods and offer novel, clever ways to measure progress in AI. Yet the system persists because it serves a purpose: in the absence of perfect measurement, approximate measurement is still better than no measurement at all.

Brooks saw this coming. "We underestimate the difference between demonstration and deployment," he wrote. "A system that works in the lab is very different from a system that works in the world."

But the benchmarks live in the lab. The leaderboards measure demonstrations. And demonstrations, optimized and polished and gamed, have become the simulacra we mistake for the real thing.

The leaderboard may crown a champion. But a champion of what? And for whom? And what does it mean to win a race when the finish line measures the wrong distance, in the wrong direction, toward a destination no one actually needs to reach?

Reading Between the Rankings

The measurement crisis isn't a reason for despair. It's a reason for humility, and for smarter navigation.

None of this means the rankings are worthless. It means they're partial truths that need context, useful signals that become dangerous when mistaken for complete information. Used correctly, benchmarks and leaderboards remain valuable tools for rough comparison, for identifying obviously deficient systems, and for tracking broad trends. Used incorrectly, they become incentive structures that warp the entire development trajectory of artificial intelligence.

Here's how to read the scoreboard without being misled by it:

1. What's actually being tested?

Not all rankings measure the same thing, and the differences matter enormously. LMArena's overall leaderboard captures general chat capability, but skews heavily toward creative tasks. If you prompt it with "write me a story" or "help me brainstorm ideas," you're feeding it exactly the kind of task it was optimized for. The coding arena tests programming tasks, but not software engineering. The "hard prompts" arena focuses on complex reasoning, but the style effects remain, meaning verbose models still have an advantage.

Before trusting any ranking, ask: is this benchmark testing what I actually need? A model that excels at creative writing might be hopeless at structured data analysis. A model that aces standardized tests might fail at open-ended research. The word "intelligence" on a leaderboard obscures more than it reveals.

Look for category-specific rankings. If you're hiring a model to write code, check benchmarks like HumanEval and SWE-bench, not general chat performance. If you're analyzing financial documents, find benchmarks that test reading comprehension and numerical reasoning, not creative storytelling. The best model overall is rarely the best model for your specific use case.

2. Who's judging?

The identity of the evaluator shapes the evaluation. Crowd voting captures what feels right to a broad audience: useful for consumer applications, misleading for specialized work. Expert evaluation captures what is right in a domain: essential for high-stakes applications, expensive to scale. Automated evaluation using model-based judges captures consistency but inherits the biases of whichever model is doing the judging.

Consider AlpacaEval, a popular automated benchmark where GPT-4 judges other models' responses. Sounds objective, right? But researchers discovered that models could game AlpacaEval by generating responses in the style GPT-4 preferred. These were longer, more formatted, more comprehensive, regardless of accuracy. Llama models initially showed inflated AlpacaEval scores because they'd learned GPT-4's aesthetic preferences, not because they were actually more capable.

When crowds judge, you get crowd preferences: friendliness over accuracy, confidence over calibration, engagement over efficiency. When experts judge, you get domain-specific quality: precision, correctness, appropriate uncertainty. When models judge, you get whatever biases the judge model has, plus a tendency toward verbose, over-explained responses because that's what training data for "helpfulness" tends to include.

None of these approaches is wrong. They're different instruments measuring different things. The error is treating them as interchangeable.

3. How recent and how confident?

In AI, months are like dog years. A model that ranked first in June might be obsolete by September. The field moves fast enough that historical rankings lose relevance almost immediately. Always check when the evaluation was conducted and whether the model version being ranked is still available.

Moreover, check the confidence intervals. In Elo-based systems, every rating comes with uncertainty.

A model rated 1,200 ±50 is statistically indistinguishable from a model rated 1,180 ±45. The

rankings display them as 5th and 8th place, but that gap is well within measurement noise.

The LMArena leaderboard displays confidence intervals, though many users ignore them. When the top ten models all have overlapping confidence ranges, there is no "best" model in any meaningful sense. There's a cluster of roughly equivalent systems, and any ranking within that cluster is arbitrary.

This matters because labs will trumpet moving from 6th to 4th place as a major achievement when both positions are within the same statistical tie. Untrained eyes then repeat these claims as if they represent real capability gaps. They don't.

Even more problematic: models with few comparisons have wide confidence intervals, which the ranking algorithm accounts for by sampling them more often, which tightens their intervals, which makes them seem more reliably positioned, which affects how often they get sampled in the future. A model's ranking is partly determined by how much data the system has collected about it, independent of actual capability.

4. Does it match your use case?

This is the most important question and the most commonly skipped.

The general "best model" might be terrible for what you specifically need. Here's a practical guide:

- For writing and creative tasks: Arena rankings are probably useful. The crowd's aesthetic preferences align reasonably well with general audience appeal. But check examples: some high-ranked models have a distinctive style that might not fit your voice.

- For coding: Ignore the main arena. Check HumanEval, which tests whether models can write correct functions, and SWE-bench, which tests whether they can solve real GitHub issues. Even these have limitations (they don't test code review, debugging, or system design) but they're more relevant than chat rankings.

- For analysis and research: Look for reasoning benchmarks like GPQA (graduate-level science questions where even PhDs struggle) or MATH (competition mathematics). Also test directly with your own domain's questions, because general reasoning benchmarks may not transfer to specialized domains.

- For enterprise applications: Ignore public benchmarks almost entirely. Run your own evaluations on your own data, in your own workflow, with your own success metrics. The correlation between leaderboard position and enterprise utility is weak. What matters is whether the model integrates well with your systems, handles your edge cases, maintains appropriate uncertainty, and fails gracefully when it fails. If you would like some help to do this, feel free to reach out!

- For safety-critical applications: Require third-party audits, not self-reported benchmarks. Look for red-team results, adversarial testing, and systematic evaluation of failure modes. The models that rank highest on capability benchmarks are not necessarily the safest or most reliable.

There are TONS of benchmarks out there for all kinds of tasks. I mention a few here as examples, but by no means is this exhaustive advice. If you have a favorite benchmark for a specific task, feel free to let me know!

Benchmarks will always have limitations. They're simplified proxies for complex phenomena. The key is understanding what they do measure well (relative performance on specific task types, rough capability tiers, obvious deficiencies) and what they don't (absolute capability, suitability for your use case, real-world reliability). Static benchmarks get contaminated; dynamic benchmarks introduce style biases and sampling issues. Crowd evaluation captures broad preferences; expert evaluation captures domain accuracy. Every approach trades some problems for others.

The goal isn't to find the perfect benchmark, it doesn't exist. The goal is to understand what each benchmark tells you and what it doesn't, then triangulate across multiple sources of information. Treat rankings as rough guides that narrow your search space, not as definitive answers that eliminate the need for your own evaluation.

What we actually need isn't one better leaderboard, but rather a more mature relationship with the leaderboards we have. That means:

- Better transparency: publishing all test runs rather than just successful ones. Reporting confidence intervals prominently. Disclosing how many private iterations happened before public release. Some companies are moving this direction, e.g. Hugging Face's Open LLM Leaderboard https://huggingface.co/open-llm-leaderboard publishes full result sets, but it needs to become standard practice.

- Richer information: not just overall rankings, but detailed breakdowns by task type, capability dimension, and use case. "Evaluation cards" that work like nutrition labels, i.e. structured summaries of what was tested, how, by whom, with what limitations, and what the results actually tell you versus what they don't.

- Diverse evaluation: the HELM benchmark tests 42 different scenarios across 59 metrics. BigBench crowdsources difficult tasks that current models fail. The AI Safety Benchmark consortium focuses specifically on potential harms. These efforts complement rather than replace simpler leaderboards, and using them together provides a fuller picture than any single metric could.

The field is learning, gradually, that intelligence, artificial or otherwise, resists easy quantification. That's not a bug in evaluation systems. It's inherent to the phenomenon being measured. The best path forward isn't perfecting measurement but rather becoming more sophisticated about interpreting imperfect measurements.

The long game

Twenty years ago, Eduardo Saverin wrote a chess formula on a window, and it helped launch a social network that would reshape how humans connect. The formula worked because rating college students was simple: people could agree, roughly, on attractiveness. The criteria were shallow but consistent.

While the story is surely apocryphal, today, that same formula sits at the heart of a much harder problem: rating the intelligence of artificial intelligence itself. Not the "narrow" intelligence of chess, where victory is unambiguous, but the sprawling, multifaceted, context-dependent intelligence we're trying to build into machines that will help us write, reason, create, and decide.

The challenges we're experiencing aren't really about LMArena or any particular benchmark. They're about the gap between our ambitions and our instruments. We want to build systems with broad capabilities, but we struggle to measure those capabilities comprehensively. We want models that truly understand, but we can mostly only test whether they perform. We want to know which system is "best," but we're still learning what "best" should mean in different contexts.

Mark Zuckerberg's company learned this the hard way. They built a model that won the ranking game and lost the utility game, and the disconnect exposed what many in the field had quietly suspected: the scoreboard doesn't measure what we think it measures.

The lesson isn't that benchmarks are broken or that leaderboards are worthless. It's that they're tools with specific uses and specific limitations. Elo works beautifully for chess because chess has one dimension of skill, played under consistent rules, with unambiguous outcomes. AI capability has many dimensions, operates across wildly different contexts, and succeeds or fails in ways that depend entirely on what you're trying to accomplish.

This matters because the stakes are high. These systems are moving from research curiosities to infrastructure: tools that will help doctors diagnose, lawyers research, students learn, and businesses operate. Getting the evaluation wrong doesn't just mean backing the wrong horse in a technology race. It means potentially building the wrong technology entirely, optimizing for benchmarks that measure charisma when we need competence, favoring systems that impress in demonstrations over ones that work reliably in deployment.

The path forward isn't finding the one perfect benchmark. It's developing the wisdom to use imperfect benchmarks well. That means understanding what each one actually measures, checking multiple sources before drawing conclusions, matching evaluation methods to your specific needs, and never letting a number substitute for your own testing and judgment. We already do this, as best we can, meaning in deeply flawed ways, in many other aspects of our society.

For the labs building these systems, it means resisting the siren call of optimization for its own sake. A model that ranks first on every benchmark but fails in real applications hasn't actually succeeded. The hardest part of engineering has always been defining success correctly before you start building.

For everyone else, the people choosing which AI to use, the executives making purchasing decisions, the policymakers writing regulations, the investors allocating capital, it means developing sophistication about what rankings can and cannot tell you. Treat them as rough guides, not gospel. Look past the headline number to understand what was tested and how. And remember that the model that wins crowd votes might not be the one that solves your problem.

The machines are getting more capable, undoubtedly. But using them wisely, i.e. knowing when to trust them, where they fall short, which one fits your needs, that remains an irreducibly human problem. The leaderboards can inform that judgment. They cannot replace it. And perhaps recognizing that limit is the first step toward building evaluation systems that actually serve their purpose: not crowning champions, but helping us understand what we've built and whether it's what we actually need.

Eduardo Saverin's window formula helped answer a simple question: who wins? The questions we're asking now are far more complex: what does it mean to be intelligent? How do we measure understanding? What makes one system better than another for a specific purpose? These aren't questions that benchmarks can fully answer. They're questions that require judgment, context, and constant refinement as the technology evolves.

And, of course, the final one: are we sure this is really a good idea?