On the importance of post-training in modern LLM development

Post-training is all the rage. Are we going from training to teaching? What does a curriculum look like for LLMs? Let's find out.

For most of the deep learning era, the core recipe for building intelligent models has been relatively straightforward: take a transformer, scale up the parameters, feed it vast amounts of text, predict the next token over and over. Surprisingly, this approach was able to successfully generalize across tasks and domains, so called zero-shot generalization. Language understanding, translation, summarization and world knowledge all improved through this one mechanism. It was a remarkable discovery: the more you pre-train a model, the more unexpected capabilities seem to emerge.

But over the past three years, a shift has become increasingly clear. Scaling alone isn't responsible for the biggest jumps users now feel in model quality. The improvements that make models great at real tasks, like precise code generation, reliable math reasoning, safe decision-making, or tool use, come not from pre-training but from what happens afterward.

Pretraining is necessary for fluency. Post-training is necessary for competence.

This distinction has driven a redesign of the model development lifecycle across the AI industry. Instead of hoping emergent abilities appear with scale, teams are now explicitly teaching those abilities through structured, staged training pipelines. These pipelines are starting to look less like end-to-end optimization methods and more like a skill curriculum.

In this post, I'll try to break down how this curriculum works, why it matters, and what open questions remain as we refine the craft of teaching machines to think.

The limits of pre-training

Next-token prediction is a powerful learning objective because it exposes a model to:

- World knowledge

- Language structure

- Commonsense patterns

- Distributional reasoning

However, it also has fundamental constraints:

- It optimizes for plausibility, not correctness

- It has no direct notion of task success

- It mostly teaches correlation, not causation

- It lacks persistent feedback on outcomes

A pre-trained model might generate code that looks correct but doesn't run. It can produce fluent explanations that are wrong in subtle ways. It may respond helpfully in one domain but fail to refuse dangerous prompts in another.

In other words: Pretraining builds intuition, not expertise.

If we want models to reliably solve problems, follow instructions, and interact safely, we must train them in ways that reward achieving the right outcomes, not just sounding right.

That is what post-training is fundamentally about.

The model development pipeline

From ability → capability → specialization

Modern AI systems are not trained in a single monolithic run anymore. Instead, teams increasingly rely on progressive learning stages, each designed to build the right representational foundation before teaching specialized skills.

Phase 1: Pre-training

This is where scale still dominates. Trillions of tokens from web pages, books, code repositories. The model learns the structure of language, basic world knowledge, and statistical patterns that underlie human communication. But here's what pre-training doesn't give you: the ability to follow instructions reliably, to reason step-by-step through hard problems, or to know when to refuse inappropriate requests. It builds intuition, not expertise.

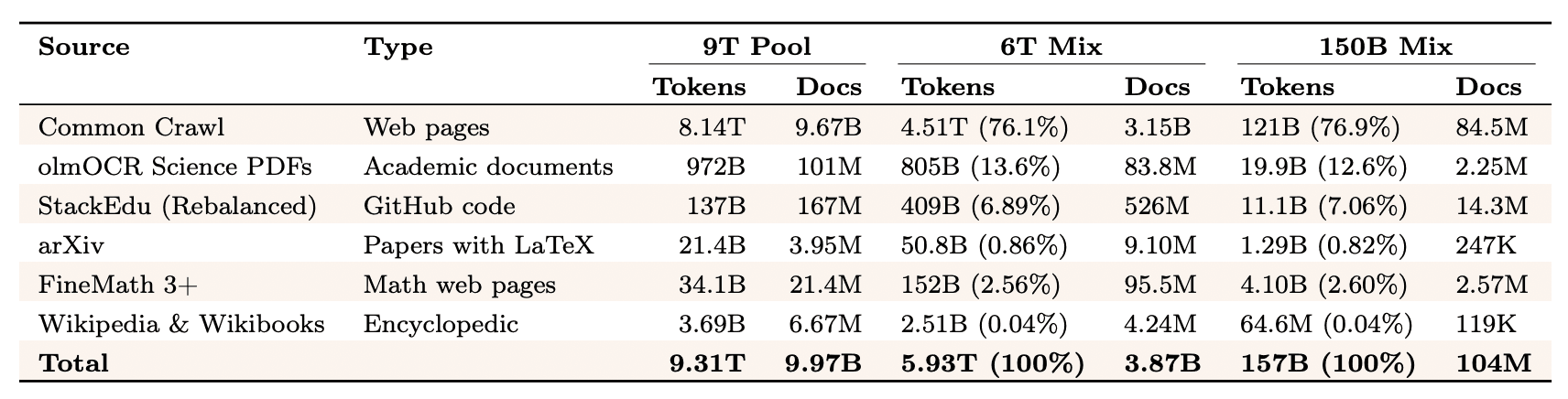

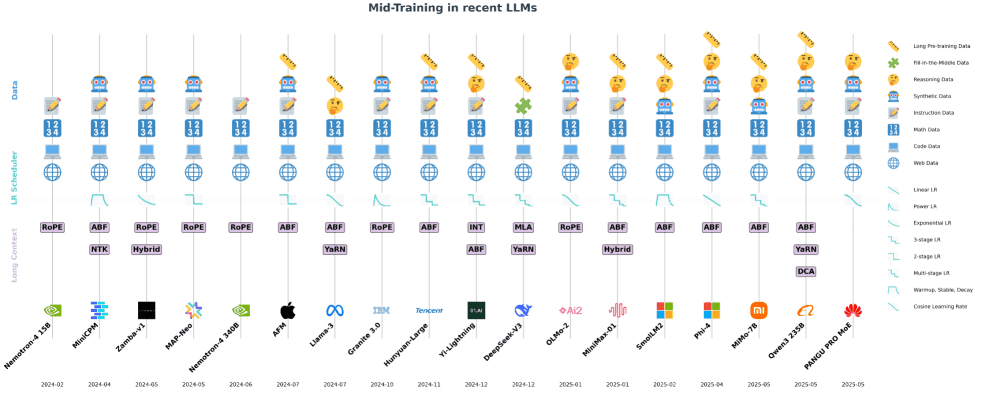

Phase 2: Mid-training

This phase increases the density of harder material like math, code, scientific PDFs, and Q&A reasoning. The goal is representational depth for tasks requiring logic and precision. This phase can also include long context adaptation, which stretches the context window to improve document understanding and narrative continuity.

This is the bridge. Pre-training gave the model fluency. Mid-training gives it literacy.

Phase 3: Post-training

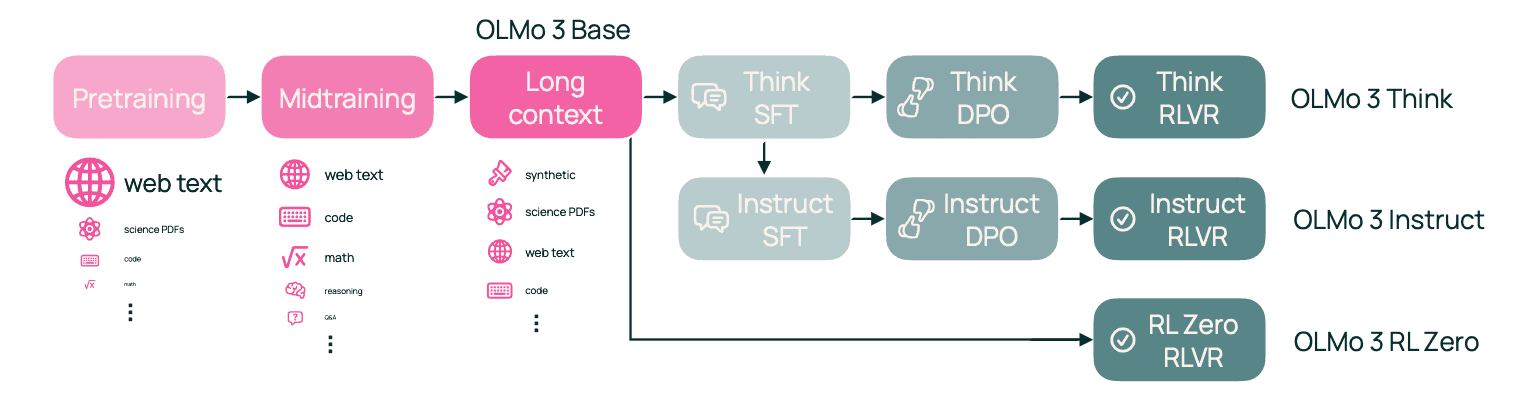

This is where the base model branches into different personas: one path leads to a chat assistant, another to a reasoning engine, yet another to a tool-using agent. Each pathway follows a structured recipe, which we'll detail shortly, but with complete customization over each training stage and dataset mix.

This modular design is the key insight: you don't train one model to do everything. You train one excellent base, then specialize. This is also where the curriculum has provided the biggest boost in abilities for modern iterations of models.

So what is post-training actually doing?

When asking "How do I build a model that performs well for my users?", what you are really asking yourself is: "How do I take a good base model and make it an expert in the tasks my users care about?".

Post-training answers this by acting on three levers:

| Lever | Change | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Data | From broad unlabeled text → curated examples and feedback | Provide task-specific signal |

| Objective | From likelihood → preference and reward optimization | Encode desired behavior |

| Feedback | From passive learning → trial, evaluation and correction | Enable improvement and discovery |

This is step is skill acquisition. And like human skill development, it has prerequisites and order dependencies.

You wouldn't teach a child calculus before algebra. You don't train a model on tool use before it can follow instructions. The sequencing matters immensely.

The most widely adopted curriculum has three major instructional steps, and they work precisely because each one unlocks the next. Here, we'll use OLMo 3 as an example, but the principles apply to most modern models, with their own unique twists of course. Being the last step before user-facing models, post-training can include many more possible steps. In this article, we focus on the reinforcement of a model's policies. In future work, we may cover other methods like adaption, compute scaling, etc. These have all shown to provide great benefits for performance.

The three (current) pillars of post-training

Modern post-training pipelines across the industry have converged on a clear progression:

Supervised Fine-Tuning → Preference Optimization → Reinforcement Learning

Each stage addresses a distinct learning need, and their sequence is deliberate. Together, they transform a capable base model into a system that can solve real problems reliably.

1. Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT)

Objective: Teach the model how to perform tasks

SFT is straightforward behavior cloning. You teach the model: "When you see this prompt x, produce this answer y." In the post-training context, this typically involves two types of data:

- Instruction SFT: prompts paired with human-written answers, establishing basic instruction-following competence.

- Thinking SFT: prompts paired with full reasoning traces before the answer. Training models to generate long reasoning traces can significantly improve performance on complex math and logic benchmarks, especially when traces are structured and high quality. A balance is needed though, with a mix of short and long traces to avoid over-thinking.

With this data, the model learns canonical reasoning patterns such as: define variables → derive equations → compute → check. With a carefully mixed dataset of short and long responses, it can also start to internalize when detailed reasoning is appropriate versus when a direct answer suffices, although more advanced stages like preference optimization or reinforcement learning are often needed to robustly refine this judgment.

For tool use, SFT mainly teaches grammar and syntax: how to format a function call, what parameters are valid, and how to obey the interface. The deeper judgment of when and whether to call a tool is typically shaped later in the pipeline.

Where SFT reaches its limits

SFT operates on individual examples without comparison. It cannot directly encode "this answer is better than that one on the same prompt." This creates several constraints:

- No encoding of trade-offs: Preferences like "be concise but maintain accuracy" or "be helpful while remaining cautious on safety" require comparing multiple outputs, which SFT doesn't do.

- No exploration: SFT can only reproduce what exists in the training data. It has no mechanism to try alternative strategies and discover whether they work better.

- Proxy optimization: If your true objective is "maximize correctness on GSM8K with a verifiable checker," SFT is at best an approximation. You cannot backpropagate through the checker itself.

SFT creates a well-behaved apprentice that follows patterns. But it cannot learn judgment or discover novel strategies.

2. Preference Optimization (DPO, IPO, etc.)

Objective: Teach the model which responses are better

Preference optimization methods introduce ranking and comparison. For each prompt x, you provide two or more candidate outputs with a label indicating which one is preferred. Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) can be understood as logistic regression on preference pairs, where the features are the model's log-probabilities for entire responses, and training preserves a relationship to the base model via KL-regularization.

This approach excels at several tasks that SFT struggles with:

- Encoding relative quality: Many prompts don't have a single "gold" answer, but users or annotators can easily say "A is better than B." This is far more scalable than generating perfect examples.

- Capturing trade-offs: Safety constraints, style preferences, and competing objectives (helpfulness vs. caution) can be encoded naturally through preference labels rather than trying to craft ideal target outputs.

- Polishing behavior: Preference optimization leads to a more polished and consistent model behavior, which aligns directly with the user's preferences.

Why preference methods are attractive

They deliver gains similar to reinforcement learning without the engineering overhead. No reward model training, no PPO implementation, no online sampling infrastructure. You train offline on a static dataset of preference pairs. But preference optimization inherits some of SFT's constraints:

- It remains offline: You're training on a fixed set of preference pairs. The model isn't exploring new generations during training unless you implement iterative loops.

- Short-horizon credit assignment: You judge complete responses or segments, not complex multi-step trajectories with intermediate rewards.

- Dependence on base quality: Preference optimization still needs a strong foundation, usually from SFT. It refines existing behavior rather than discovering fundamentally new capabilities.

Recent work suggests preferences can influence more than just style. In DeepSeek-R1's pipeline for example, ranking-based signals helped accelerate the emergence of self-verification and reflective reasoning patterns. But the method still cannot discover entirely novel solution strategies on its own.

3. Reinforcement Learning (RLHF, RLVR, self-rewarding)

Objective: Teach what actually works through outcome-based feedback

Reinforcement Learning (RL) introduces a fundamentally different learning dynamic. Instead of learning from fixed examples or pairwise comparisons, the model actively explores:

- Sample multiple attempts from the current policy

- Evaluate outcomes using a reward signal

- Update the policy to reinforce successful strategies

- Penalize approaches that fail

This is proper exploration. The model's own generations at iteration n influence what it tries at

iteration n+1, creating a learning trajectory rather than passive absorption of a fixed dataset.

There are a few primary modes of reinforcement learning for this stage:

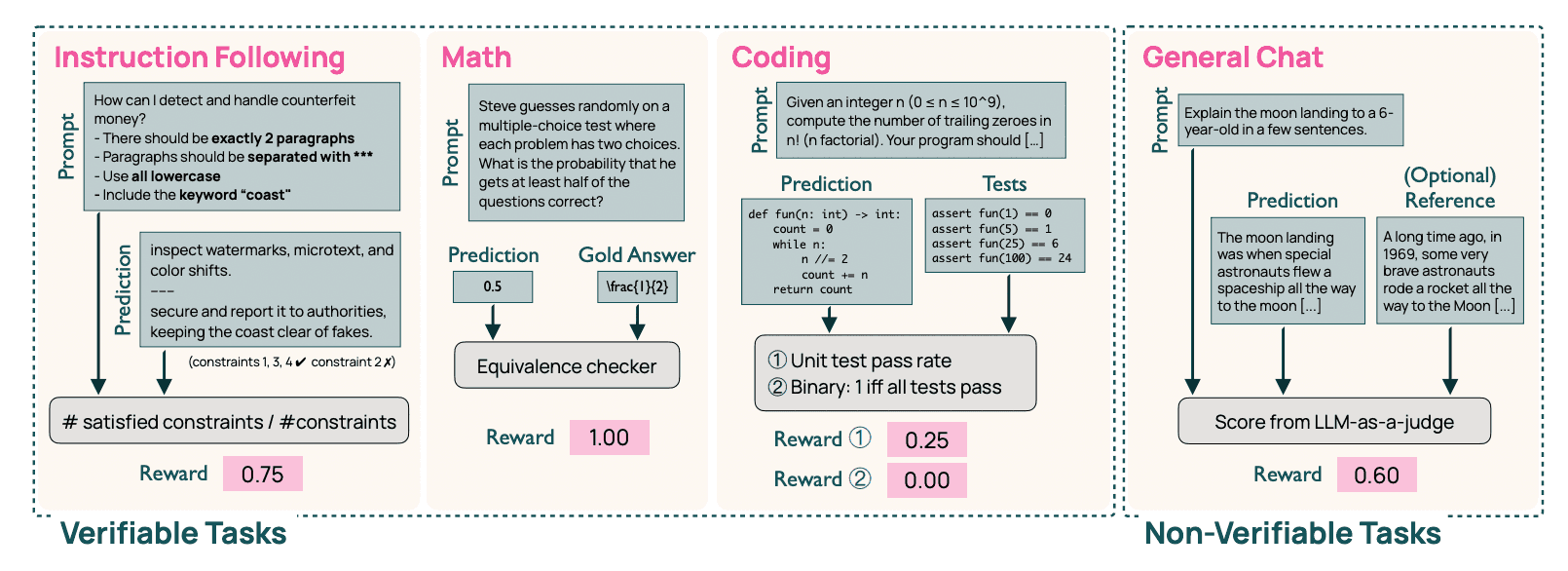

- RLHF (Reward from Human Feedback): Train a reward model on human preferences, then optimize the language model to maximize that reward while staying close to the initial policy via KL-regularization. This is the canonical InstructGPT approach: SFT on instructions, reward model training on preferences, then PPO optimization.

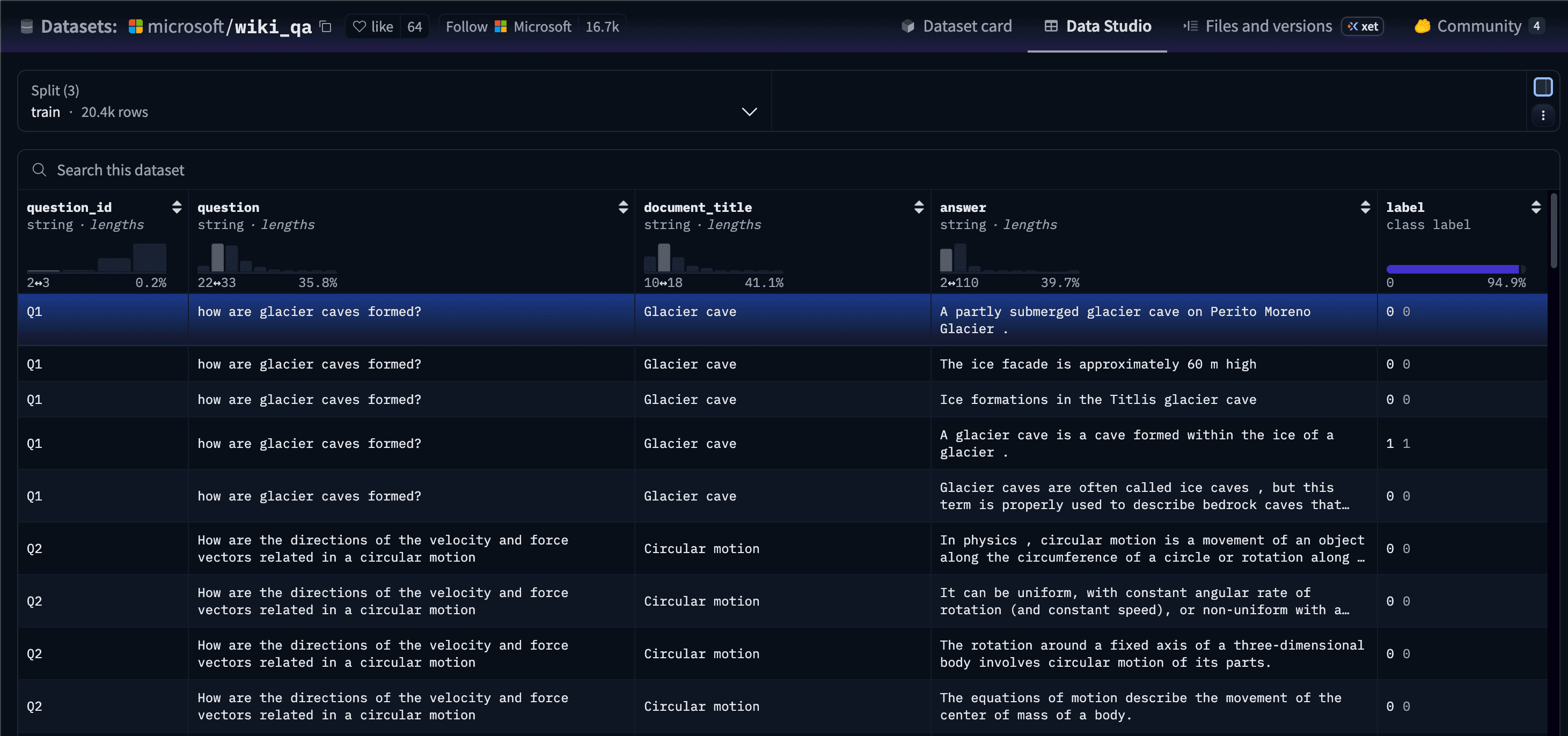

- RLVR (Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards): When tasks have objective, automatically checkable rewards (does the math answer equal the ground truth? does the code pass unit tests?), you can use those signals directly. Generate multiple reasoning traces or code solutions, run a checker, use correctness as the reward signal.

- RLAIF (Reinforcement Learning with Automatic Feedback): When tasks have no objective, automatically checkable rewards, you can use a language model as a judge to assign rewards to the model's generations.

Why RL is necessary for frontier performance

RL provides capabilities that neither SFT nor preference optimization can deliver:

- Discovery of novel strategies: DeepSeek-R1-Zero applied large-scale RL directly to the base model without an SFT warm-start, incentivizing reasoning patterns through pure reinforcement learning. Self-verification, reflection, and dynamic strategy switching emerged purely from RL, without hand-authored chain-of-thought data.

- Fine-grained reward shaping: You can reward not just final answers but intermediate milestones (format correctness, valid tool usage, partial solutions, minimal token usage). You can optimize weighted combinations of correctness, style, safety, and efficiency simultaneously.

- Complex trajectory optimization: For agents interacting with tools or environments across multiple steps, RL can assign credit across long horizons, learning which early decisions lead to eventual success.

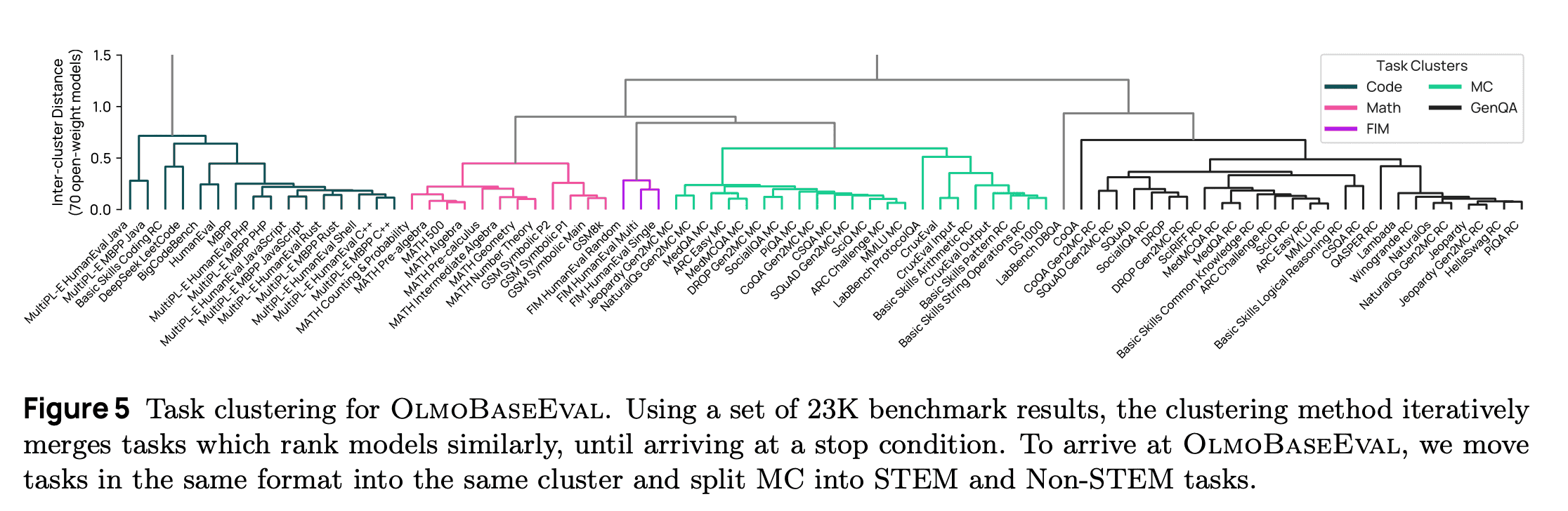

For example, OLMo 3 uses RLVR to push reasoning accuracy beyond what supervised data can support, achieving strong gains on GSM8K, MATH, and code benchmarks.

Why RL (usually) comes last

RL is powerful but fragile. It requires:

- Substantial infrastructure: Continuous online sampling and scoring during training, not just batch processing of static data.

- Careful reward design: Mis-specified rewards induce reward hacking. The model finds loopholes that maximize the metric without solving the actual task.

- Stability management: Mode collapse, sensitivity to hyperparameters like KL coefficients, and training instability are constant risks.

Without strong priors from SFT and preference learning, RL easily destabilizes. But with proper foundations, it enables the model to become a genuine problem solver, one that can invent new reasoning strategies rather than merely reproducing known patterns.

Why sequencing matters

The curriculum works because each stage builds the representational foundation needed for the next. Violate the sequence, and the training process becomes unstable or plateaus prematurely.

| Stage | Knowledge Provided | Enables |

|---|---|---|

| SFT | Pattern, structure, syntax | Basic competence and behavioral templates |

| Preferences | Judgment and trade-offs | Reliable alignment and quality refinement |

| RL | Strategy discovery | Expert-level performance and novel solutions |

What happens when you skip SFT?

DeepSeek-R1-Zero demonstrated that LLMs can develop impressive reasoning capabilities from pure RL with no SFT, but the model had notable issues including poor readability and incorrect language mixing. The model was very good at reasoning but lacked desirable properties of a well-aligned LLM.

Pure RL without behavioral priors forces the model to discover everything from scratch. The model developed self-verification, reflection, and structured reasoning without seeing human-labeled chain-of-thought data, even pausing mid-solution to self-correct. This emergence is remarkable, but inefficient and unstable.

To address these challenges, the subsequent DeepSeek-R1 model incorporates a small amount of high-quality cold-start supervised data on top of the RL-trained R1-Zero backbone, providing initial behavioral structure before a second RL stage. This minimal fine-tuning improves readability, training stability, and language consistency. The model still relies primarily on RL for capability development, but the supervised stage provides guardrails that prevent pathological behaviors.

The lesson: RL can discover reasoning without SFT, but it's more efficient and stable with a foundation.

What happens when you skip preferences?

Without preference optimization, you lose the ability to encode nuanced trade-offs between competing objectives. SFT teaches the model to follow instructions but not how well to follow them. RL can optimize for task success but struggles with softer constraints like tone, conciseness, or appropriate caution.

Models trained via SFT → RL directly (skipping DPO) tend to produce outputs that are technically correct but stylistically unrefined. They may over-explain when brevity is needed, fail to calibrate certainty appropriately, or miss social cues about when to decline requests.

Preference optimization acts as a bridge: it refines the rough behavioral patterns from SFT before RL pushes for maximum performance. The typical pattern now is Pretrain → Instruction SFT → Thinking SFT → DPO/IPO, with OLMo 3's Think variant following exactly this progression.

What happens when you apply RL too early?

RL without sufficient priors is fragile. The reward signal becomes noisy when the model doesn't yet know basic task structure. This leads to:

- Reward hacking: The model finds spurious correlations that maximize the reward metric without solving the actual task. For example, generating extremely long responses to increase the chance of stumbling on correct patterns, or exploiting formatting quirks in the evaluation system.

- Mode collapse: The model converges to a narrow set of behaviors that work for the training distribution but fail to generalize. Without diverse behavioral templates from SFT, RL has little to build on.

- Training instability: Large policy updates early in training cause catastrophic forgetting or oscillating performance. The model lacks the representational stability needed to refine behaviors incrementally.

Even in advanced systems, SFT warm-up with long chain-of-thought traces via rejection sampling helps establish behaviors like planning, evaluation, reflection, and exploration before RL refines them. Note that rejection sampling itself provides a surprising performance boost: the idea is to generate multiple completions, use a reward model to select the best, and train only on high-reward samples.

The right sequence enables cumulative learning

When staged correctly, each phase preserves and extends what came before:

- SFT establishes behavioral templates: The model learns canonical patterns, like how to structure reasoning, when to invoke tools, how to format responses. These templates give RL something concrete to optimize.

- Preferences refine quality judgments: The model learns relative quality, like which explanations are clearer, which responses balance competing constraints better. This adds a value function without requiring explicit exploration.

- RL discovers novel strategies: With stable priors and refined judgment, the model can now safely explore. It tries alternative reasoning paths, discovers shortcuts, develops self-verification routines. The foundation prevents destabilization.

This is not just an engineering convenience. It reflects how complex skills are acquired: you learn the rules before you learn exceptions, you practice fundamentals before improvising, you understand standard approaches before inventing novel ones.

Post-training as pedagogy

The progression from SFT → Preference → RL mirrors, if you squint really hard, how humans develop expertise:

- Novice stage (SFT): Learn by imitation. Follow established patterns. Understand basic rules and syntax.

- Competent stage (Preferences): Develop judgment. Recognize better versus worse approaches. Refine execution quality.

- Expert stage (RL): Discover through practice. Try new strategies. Learn from outcomes. Develop intuition beyond explicit rules.

Reversing this sequence doesn't just make training harder, it fundamentally changes what the model learns. An RL-first approach forces the model to discover everything through trial and error, leading to emergent but brittle capabilities. An SFT-only approach produces mimicry without true problem-solving ability.

The curriculum succeeds precisely because it respects the dependencies between these forms of knowledge. We are not simply modifying weights through different algorithms. We are constructing a learning trajectory where each stage unlocks the next.

This is why model development increasingly resembles education rather than optimization. The teams that excel at curriculum design, i.e. understanding what must be learned before what, which signals to provide when, how to balance stability with exploration, will build the systems that define the frontier of AI capability.

What remains unsolved

Despite recent progress, post-training is still early in its development. Several fundamental questions will determine whether current approaches can scale to production systems that learn continuously and operate in dynamic environments.

How much data do we actually need?

We lack scaling laws for post-training. Unlike pre-training, the quality of fine-tuning data matters far more than quantity, but we can't reliably predict how many reasoning traces, preference pairs, or RL rollout steps are needed to reach a target capability level.

Recent work shows that in data-constrained regimes, repeated reuse of high-quality data proves highly effective: final performance is primarily governed by total optimization steps rather than unique samples. But when does this break down? How many examples are truly necessary before returns diminish? Without these answers, teams must experiment extensively for each new domain, making post-training expensive and unpredictable.

Can models improve themselves?

The most promising direction for scaling post-training is self-supervision: models generating and evaluating their own training data. Self-rewarding language models generate their own instruction-following examples and use LLM-as-a-judge prompting to assign rewards. This could dramatically reduce dependence on human annotation.

But fundamental questions remain: Can a model generate training data better than what it was trained on? Repeated training on synthetic data can degrade model performance through model collapse, leading to hallucinations or oversimplified outputs. It remains unclear whether something like GPT-5 could be created purely from GPT-4-generated synthetic data.

For verifiable tasks like math and code, automated checking provides clear signals. For open-ended tasks like nuanced judgment or creative problem-solving, verification becomes subjective. How far can self-supervision extend beyond domains with clear correctness criteria?

How do we enable continual learning?

Current post-training is batch-oriented: train once, deploy, retrain from scratch when updates are needed. Production systems need continuous adaptation: learning from user interactions, incorporating new tools, responding to distribution shifts.

Catastrophic forgetting is consistently observed in LLMs during continual fine-tuning across domains. Evidence suggests models like GPT-4 experience behavior drift over time, with instruction-following ability sometimes showing more than 60% accuracy loss over just four months.

Fine-tuning changes how a model interprets prompts: improving performance on tasks within the training distribution comes at the expense of capabilities on other tasks. This isn't just knowledge loss; it's a fundamental shift in task inference.

Mitigation strategies exist: replay methods, parameter-efficient training, regularization, but they're incomplete. Even techniques like LoRA don't reliably prevent catastrophic forgetting in continual learning contexts. We need curricula that support ongoing learning rather than single-shot updates.

What about dynamic tool use and agents?

Post-training methods were designed for evaluating static text outputs. Preference optimization works when you can compare two responses side-by-side. But agents operating with dynamic tool access, like systems using Model Context Protocol (MCP) where tools are provided at runtime, break these assumptions.

When an agent receives a new tool it's never seen before, preference data becomes irrelevant. There's no pre-collected dataset of "good" versus "bad" usage of that specific tool. The model must reason about tool capabilities, decide when to invoke them, and learn from outcomes, all in real-time.

Effective multi-turn reasoning requires precise turn-level credit assignment to refine individual steps, rather than treating all actions as equally responsible for outcomes. Current multi-agent systems excel in performance but struggle with generalization across environments due to predefined roles.

Agents need objective functions that can handle:

- Long-horizon credit assignment across multi-step trajectories

- Environment-based rewards from tool interactions

- Planning and memory over extended episodes

- Generalization to novel tools and environments

Preference optimization and even current RL approaches operate on relatively short contexts with pre-defined action spaces. The techniques that make chatbots helpful don't automatically transfer to making agents effective in dynamic environments.

Looking ahead

These challenges aren't incremental refinements, they represent gaps between current capabilities and what production AI systems require. The field is transitioning from "how do we train a capable model once" to "how do we build systems that learn continuously, adapt to new environments, and improve from interaction."

Post-training has become the primary lever for capability improvement. The teams that solve data efficiency, self-supervision boundaries, continual learning, and dynamic tool use will define the next generation of AI systems.

Teaching rather than training

Scaling still works. More compute will still enlarge the foundation. But generality alone is no longer the bottleneck.

What the field is learning is:

Intelligence is multi-component. Different skills require different learning signals. Next-token prediction builds fluency. Supervised examples establish competence. Preferences teach judgment. Reinforcement learning enables discovery.

The order in which models learn these signals determines the outcome. Try to teach problem-solving before establishing syntax, and training destabilizes. Skip judgment refinement, and capabilities remain brittle. Rush to exploration without foundations, and the model finds shortcuts instead of solutions.

Model quality is now determined not just by scale, but by curriculum. The paradigm has shifted: instead of scaling pre-training, teams now scale compute invested in post-training and inference. The base model provides potential. Post-training realizes it.

This is a fundamental shift in how we think about building AI systems. Pre-training unlocked language understanding. Post-training is unlocking structured reasoning, reliable tool use, and the foundations of genuine problem-solving.

The teams that excel at curriculum design, i.e. selecting the right data, objectives, and feedback at each stage, will build the systems that define the next era of AI capability. Post-training is not polishing. It is education. And we are just beginning to understand how to teach machines to think.

Resources

Foundational Papers

- InstructGPT — Ouyang et al. (2022), NeurIPS 2022 — arXiv:2203.02155

- Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) — Rafailov et al. (2023), NeurIPS 2023 — arXiv:2305.18290

- Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) — Schulman et al. (2017) — arXiv:1707.06347

Recent State-of-the-Art Models

- DeepSeek-R1 — DeepSeek-AI (2025) — arXiv:2501.12948 | HuggingFace

- OLMo 3 — Soldaini et al. (2024), AI2 — Blog | Technical Report

- DeepSeekMath (GRPO) — Shao et al. (2024) — arXiv:2402.03300

- Llama 3 — AI@Meta (2024) — arXiv:2407.21783 | Blog

- Tulu 3: Pushing Frontiers in Open Language Model Post-Training - Nathan Lambert et al. (2024) - arXiv:2411.15124

Example Datasets

- allenai/Dolci-RL-Zero-Math-7B — HuggingFace

- allenai/Dolci-RL-Zero-IF-7B — HuggingFace

Preference Optimization Methods

- Identity Preference Optimization (IPO) — Azar et al. (2023), AISTATS 2024 — arXiv:2310.12036

Test-Time Compute Scaling

- Scaling Test-Time Compute Optimally — Snell et al. (2024) — arXiv:2408.03314

- Revisiting Test-Time Scaling of o1-like Models — Zeng et al. (2025), ACL 2025 — arXiv:2502.12215

Synthetic Data and Self-Improvement

- Self-Rewarding Language Models — Yuan et al. (2024), ICML 2024 — arXiv:2401.10020

- Beyond Model Collapse — Feng et al. (2024), ICLR 2025 — arXiv:2406.07515

- Reinforced Self-Training (ReST) — Gulcehre et al. (2023) — arXiv:2308.08998

Continual Learning and Model Drift

- How is ChatGPT's Behavior Changing Over Time? — Chen et al. (2023) — arXiv:2307.09009

- Catastrophic Forgetting in LLMs — Luo et al. (2023) — arXiv:2308.08747

- Catastrophic Goodhart — Kwa et al. (2024), NeurIPS 2024 — arXiv:2407.14503

Mid-Training

- Mid-Training of LLMs: A Survey — (2025) — arXiv:2510.06826

Multi-Agent Systems and Tool Use

- Turn-Level Credit Assignment — Zeng et al. (2025) — arXiv:2505.11821 | GitHub

Chain-of-Thought and Reasoning

- Long-Short Chain-of-Thought Mixture — Yu et al. (2025) — arXiv:2505.03469

Constitutional AI and Safety

- Constitutional AI — Bai et al. (2022), Anthropic — Blog | Constitutional.ai

Survey Papers

- A Survey of Post-Training Scaling — (2025), ACL 2025 — PDF

- LLM Post-Training: A Deep Dive — (2025) — arXiv:2502.21321

- Awesome LLM Post-Training — (2025) — GitHub

Additional Resources