12 Predictions for Embodied AI and Robotics in 2026

Predictions are notoriously a fool's errand. As Rod Brooks puts it in his own

yearly predictions, we are all

susceptible to FOBAWTPALSL: Fear Of Being A Wimpy Techno-Pessimist And Looking Stupid Later these

days. This fear, combined with its cousin FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out), drives herd behavior in

establishing the zeitgeist on almost any technology topic.

Now, I'm no Rodney Brooks, so I won't be able to predict the future. Having been in the space for a while though, I can say 2025 was a particularly interesting year. The sentiment around robotics and the newly minted "embodied AI" has shifted dramatically, to the point where it has now become a major political issue, a favored investment thesis, and an attractive outlet for the smartest minds in the world. We saw countless exciting (and sometimess worrying) demos, followed by spectacular failures. Throughout, the discourse has been extremely polarized, with some arguing that the sky is falling, and others that the sky is the limit.

As we enter 2026, I thought it might be fun to write down some "predictions" for the year ahead. What follows are twelve such bets. Starting with the foundational technology shifts (VLA models and how they're changing), we'll then move through the hardware and sensing that enables them, then to deployment realities, market drivers, and finally the safety and measurement challenges the field must confront.

Each prediction includes a confidence level and an explanation of why I might be wrong. I've tried to keep them specific, and falsifiable by design, so we can check on them again in January 2027. I usually get asked about these topics a lot, so I figured it might be interesting to state them plainly, and more importantly, use them as the basis for discussion. If you're interested in proving me wrong, to my face, please do! Reach out and let's chat.

Alright, let's get to it!

The Rise of VLAs: Foundation Models Come to Robotics

Before diving into predictions, some context: 2025 was the year Vision-Language-Action models went from research curiosity to the dominant paradigm in robot learning. VLAs combine pretrained vision-language models (which already understand the world from internet-scale image-text training) with action prediction, essentially giving robots a "brain" that can see, understand language, and output motor commands in a single neural network.

The key innovation is language grounding. Traditional robot learning required training policies from scratch for each task, robot, and environment. VLAs sidestep this by inheriting semantic understanding from VLMs trained on billions of image-text pairs. When you tell a VLA to "pick up the red cup near the keyboard," the model already knows what cups look like, understands spatial relationships like "near," and can connect the word "red" to visual features, all before seeing a single robot demonstration. This grounding transforms natural language commands into physical actions through a shared representational space that connects words, visual observations, and motor outputs.

VLAs promise something different: a foundation model that generalizes across tasks, responds to natural language commands, and transfers knowledge from one robot to another. Models like OpenVLA (7B parameters), π0, Helix, and GR00T N1 represent this new generation.

1. Scaling laws for VLAs will be tested in 2026

By the end of 2026, at least one VLA model with >100B parameters will be published and demonstrate state-of-the-art results on standard robotics benchmarks, with evidence of continued performance gains from scale.

In a world full of massive language models with hundreds of billions of parameters, the most advanced robot brains in the world are running tiny models in comparison. OpenVLA is 7B parameters. Physical Intelligence's π0 is 3B parameters. NVIDIA's GR00T N1 is 2.2B parameters. Figure's Helix uses a 7B parameter backbone.

Why is that?

The obvious answer would be deployment constraints: robots need to run inference on-device, and you can't strap an H100 cluster to a humanoid's chest. Still, if the bitter lesson were to hold for robotics, the incentive to scale would be enormous.

DeepMind built RT-2 at 55B in 2023 and showed real emergent capabilities: symbol understanding, novel instruction following, basic reasoning. Then... nothing. Gemini Robotics 1.5 shipped in September 2025 with impressive capabilities, but no parameter counts.

The optimistic read: we're pre-GPT-3. The field hasn't yet made the jump from "scaling probably helps" to "scaling demonstrably works and here's the curve." DiffusionVLA scaled from 2B to 72B and saw improved generalization on zero-shot bin-picking: physical manipulation, not just language tasks. That's a single data point, but it's the right shape. For the first time ever, several players have the resources to run the full scaling experiment. If that happens, we might see a phase transition like language models had.

Why I might be wrong

We don't actually know how to count data in robotics, and that might break the scaling playbook entirely. For language, LLMs train on tens of trillions of tokens, roughly 10^14 bytes. Text is low bandwidth but extremely dense. More tokens means more concepts, more relationships, more world knowledge. That's one of the reasons why scaling works.

Yann LeCun likes to point out that a 4-year-old has processed 50 times more raw data through vision than the largest LLMs see in text. But visual data is redundant, adjacent frames differ by pixels, not concepts. LeCun argues the lower information density is actually good for self-supervised learning, as the structure in video teaches how the world works. But this also means we need exponentially more data to even approach the learning capacity of language models, or we need to change current architectures and learning paradigms.

2. Multimodal VLAs will demonstrate a clear advantage on contact-rich tasks

By end of 2026, at least one peer-reviewed paper will demonstrate a VLA with integrated tactile sensing that outperforms vision-only approaches by >15% absolute success rate on contact-rich manipulation tasks.

VLAs inherit their "understanding" from vision-language pretraining, but some tasks fundamentally require touch. Unlike depth, there is currently no reliable way to detect slip, measure insertion force, or sense contact geometry through vision alone. This limits precision and completely rules out compliant control.

Multiple tactile-VLA architectures emerged in 2025, with impressive early results:

- OmniVTLA shows 21.9% improvement over VLA baselines on pick-and-place with grippers

- Tactile-VLA achieves 90% success on charger insertion versus 25-40% for π₀ baselines

- VTLA reaches 90% vs 80% for vision-only on tight-tolerance peg insertion

- VLA-Touch adds tactile feedback to existing VLAs without fine-tuning the base model

The hardware is maturing in parallel. F-TAC Hand, published in Nature Machine Intelligence, achieves 0.1mm spatial resolution across 70% of the hand surface, comparable to human tactile acuity.

The theoretical case is strong, and in general, the debate of multimodality will carry over from the self driving wars over to robotics. The community is now more and more comfortable with with monocular vision, progressively dropping lidars. Will this trend of learned physical constraints carry over to other, even more "Moravec-pilled" tasks?

Why I might be wrong

Current results cluster around insertion and pick-and-place. Tactile advantages may not transfer to the broader set of contact-rich tasks (deformable objects, assembly, tool use). Sensor calibration, latency, and fragility could prevent tactile from being a net positive in practice. And the 2025 papers are all preprints, so peer review may reveal issues with experimental methodology.

3. The competition to build robotics-specific compute hardware will intensify

By December 2026, at least one commercial robot will ship with a VLA model running entirely on-board (no cloud connectivity required for core manipulation), enabled by new edge hardware and aggressive model optimization.

As we discussed, the gap between model size in text LLMs and VLAs is massive, in parameter size but also in terms of hardware. This makes sense, you can't just strap a datacenter to a robot's chest and expect it to work out. The compute loads, the timing requirements, the power limitations are all very different.

The current lineup of hardware is still relatively weak in comparison. NVIDIA's Jetson Orin delivers ~275 TOPS with ~60 GB/s memory bandwidth. Jetson Thor promises 2,070 FP4 TFLOPS with 128GB unified memory. Sounds impressive, but memory bandwidth remains the bottleneck for transformer inference. Compare to an H100's ~3,350 GB/s or B200's ~8,000 GB/s.

Companies are currently working around this constraint for demos, but obviously it won't cut it for a real deployment. Figure for example straps dual RTX GPUs (aggregate ~1 TB/s bandwidth) to their robots to run the Helix S2 on-board. The other lever is to keep models small: 1X runs Redwood AI, a heavily distilled ~160M parameter model, on Jetson Thor. Physical Intelligence designed π0's 3B-parameter architecture specifically for edge deployment.

Combined with our first prediction, the trend is clear: more capable edge hardware will be needed to run the increasingly large models required. This will drive heavy competition for efficient, fast, dedicated hardware for embodied AI.

Why I might be wrong

If small models trained via knowledge distillation consistently outperform their larger teachers on deployment metrics (latency, power, reliability), the incentive to build robotics-specific silicon weakens. Robotics might not be the priority for chip makers anytime soon, with edge compute volumes being driven by smartphone makers. And diffusion-based action heads might prove more efficient than autoregressive transformers for motor control, shifting the compute bottleneck entirely.

4. Open-source VLAs will continue to close the gap with proprietary models

By end of 2026, at least one open-weight VLA will achieve benchmark performance within 5% of the best proprietary model on five of the most widely-used robotics benchmark.

OpenVLA (7B parameters, open-source) already outperforms RT-2-X (55B, proprietary) by 16.5% in absolute success rate. SmolVLA (450M, open-source) claims comparable performance to much larger models. New companies like UMA (founded by Remi Cadene) are popping up, following suit of the LeRobot initiatives from Hugging Face.

But the pattern from LLMs might not apply in the same way. In language, the internet provided free training data, the moat was compute. In robotics, gathering good manipulation data costs real money: hardware, operators, environments, maintenance. Proprietary labs with deployed fleets (Tesla, Amazon) accumulate data that's expensive to replicate.

Still, open efforts are mobilizing. Labs like Hugging Face's LeRobot, the Open X-Embodiment consortium, and university coalitions are pursuing the open ethos that defined early robotics research. The community remains philosophically split: Google's acquisition of the Open Source Robotics Foundation signaled that even "open" infrastructure can consolidate.

Why I might be wrong

Data costs might prove insurmountable. Either through vast capital expenditure or through "trojan horse" deployments, well funded companies could generate more data in a day than the entire open-source community collects in a year. Proprietary labs might simply stop publishing comparable numbers, making the gap unmeasurable. In the LLM world, open-source labs like Mistral publish smaller models but keep the larger ones proprietary. This pattern might carry over to embodied AI.

5. Mobile robots will continue to outpace humanoids in commercial deployments

By end of 2026, the number of mobile robots (AMRs, AGVs, mobile manipulators) in commercial revenue-generating deployments will exceed humanoid robots in equivalent deployments by at least 10:1.

Logistics, manufacturing, healthcare, food processing, energy are historically the most automation-hungry industries. Most of these tasks value automation when there is a high-volume, low-variability mix. They are usually highly controllable environments, where more reliable solutions are preferred.

In contrast, humanoids still face many fundamental challenges:

- Bipedal walking is inherently unstable and power-hungry

- The form-factor advantage for "human environments" is overstated, most industrial settings can be modified more cheaply than buying humanoids

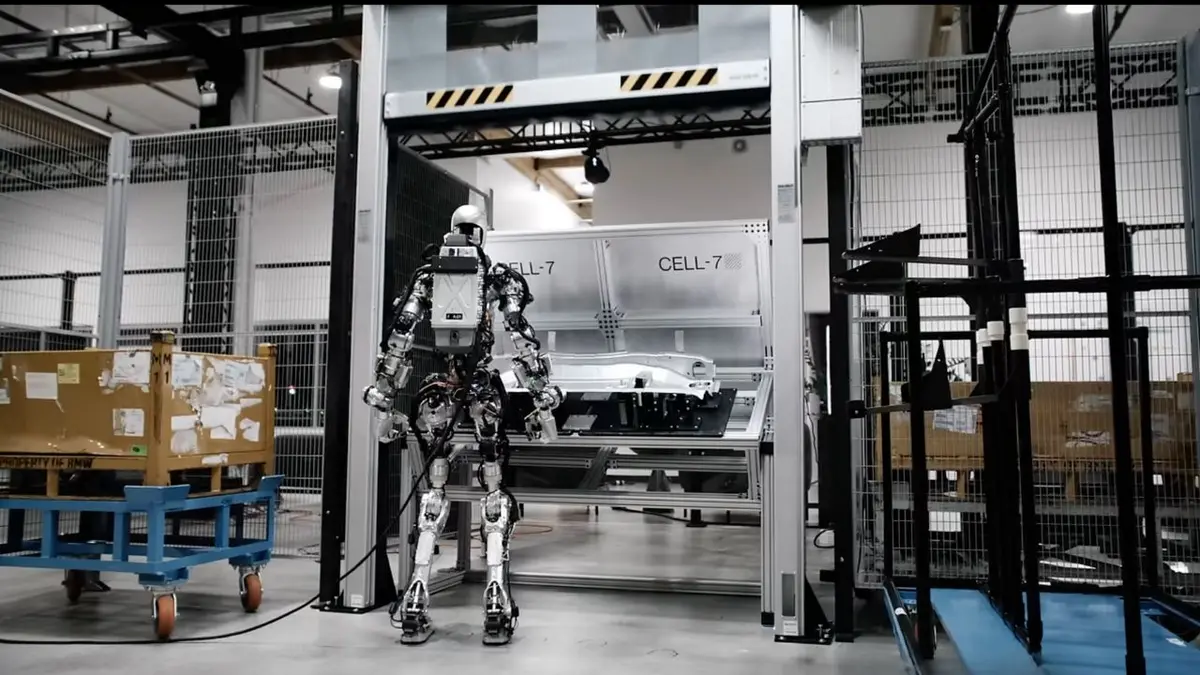

- Figure's 11-month BMW deployment involved a single robot for most of the program, doing pick-and-place tasks that don't require human form

- As Brooks notes: "the visual appearance of a robot makes a promise about what it can do." Humanoids promise human-level capability and can't deliver. Yet.

Why I might be wrong

Humanoids are the darling of the industry these days: there is real appetite, capital and brain power behind the problem. There is a huge incentive for large-scale trials, including internal efforts like Tesla's Optimus. That said, with its track record of delivering such features on time, this prediction might turn out to be pretty safe...

6. Long-horizon task chaining will remain unsolved in unstructured environments

No robot system demonstrated in 2026 will reliably (>80% pass@1 success rate) execute chains of

10+ distinct manipulation subtasks in genuinely unstructured environments without either: (a) human

intervention, (b) teleoperation for some subtasks, or (c) demonstration cherry-picking (in

environment or task completion).

This is the dirty secret of current VLA demos. Watch carefully: most impressive demonstrations are single tasks or short chains (3-5 steps) in controlled environments. Figure's Helix demo of "an hour of fully autonomous package reorientation" is a single repeated task, not a 10-step chain. Not to mention most autonomous task completions are really teleoperated.

In general, unless it is explicitly specified, you can safely assume a task accomplished by a robot is NOT autonomous.

The compound error problem is brutal: even 95% per-step reliability gives you 60% success on a 10-step chain, and 54% on a 12-step chain. Current benchmarks confirm this: RoboCasa composite tasks (requiring skill sequencing) have dramatically lower success rates than atomic tasks. VLA survey papers note that existing models "struggle to generalize beyond the training distribution" for long-horizon composition.

This isn't just a robotics problem, it's an open challenge in LLMs too. 2025 has shown fantastic progress in long task coherence, with the latest models able to run autonomously for ~30 mins. This is still a short horizon: language models still struggle with tasks requiring sustained coherence over hundreds of steps. Continual learning and long-horizon reliability will be major metrics of improvement across embodied and non-embodied AI in 2026.

Why I might be wrong

Hierarchical architectures (like Helix's S1/S2 split) might solve the planning/execution separation better than I expect. If LLM reasoning capabilities transfer to VLAs effectively, the planning layer might become good enough to compensate for execution errors. We are seeing glimpses of this with Chain-of-action architectures showing great progress, like Chain-of-thought served LLMs.

7. World models will achieve 1-hour coherent video prediction for simple robotic environments

By end of 2026, at least one published world model will demonstrate coherent video prediction (no major artifacts, physics violations, or identity drift) for 1 hour of continuous simulation of a simple robotic environment (tabletop manipulation, single room navigation, or similar constrained setting).

We started the year going from image generation, the main theme of 2023/4, to more consistent auto-regressive video models. 2025 saw the advent of new video steerable models with internally consistent world models. Nvidia's Cosmos, Deepmind's Genie 3, and other video steerable models are pushing toward longer coherence windows. Current state-of-art is roughly 5-10 minutes before degradation in simple environments.

Going from minutes to an hour will require huge improvements in internal representation consistency. The constraint to "simple environments" makes this achievable. I'm making this prediction bolder than consensus because the research trajectory suggests it's within reach.

Why I might be wrong

The jump might hit fundamental limits in autoregressive video generation. Coherence over long horizons might require explicit physics engines or symbolic reasoning that current pure-neural approaches can't provide.

8. Defense robotics investment will drive a significant increase in robotics investment in 2026

In 2026, total defense robotics investment (defense-focused VC) will grow by at least 100% year-over-year.

At this point we're all well aware of the shifting geopolitical tides. Across the world, countries are gearing up for existing and future conflicts. This has driven large spending sprees and even larger amounts of investments into defense tech. What used to be a taboo has become a point of pride and emphasis for many investors.

In Europe alone, investment in defense robotics reached $2B+ in 2025. 2025 featured some of the largest defense AI contracts awarded by the federal government, and its aptly renamed Department of War, in recent memory. The top 10 awards had a cumulative value of $38.3 billion, according to GovCon Daily research.

Every era of conflict drives massive growth into the technological frontier of its time. In our world, AI and automation are poised to dominate this new generation of warfare. New tectonic shifts in diplomatic relations also re-draws the technological collaboration map. Europe in particular is waking up to its own vulnerabilities and is pushing for way more independence, through automation as one of the levers.

Why I might be wrong

Wishful thinking would offer a chance that the global tensions never escalate to dramatic levels, though my inner skeptic finds it hard to believe.

9. Robotic fleet orchestration will become an explicit purchasing criterion

By end of 2026, at least 5 major warehouse operators (>10 facilities each) will publicly cite VDA 5050 compliance or multi-vendor fleet orchestration as explicit requirements in their robotics RFPs or procurement criteria.

Walk into a large fulfillment center today and you'll find a fleet that looks like the Island of Misfit Robots: Locus for picking, MiR for transport, Autostore for storage: three vendors, three control systems, three integration headaches. When robot A can't tell robot B it's blocking the aisle, humans intervene. VDA 5050 promises a common language. Platforms like GreyOrange GreyMatter, InOrbit, and Bosch Rexroth ctrlX are betting that "buy best-of-breed, orchestrate centrally" becomes the default architecture.

A related shift: natural language is becoming the interface for fleet operations. Instead of programming waypoints, operators describe tasks in text. This lowers the barrier to entry since you don't need robotics engineers to retask a fleet, while generating valuable training data for the next generation of models. The orchestration layer becomes a data flywheel.

Why I might be wrong

Enterprise sales cycles are long; RFPs written in 2026 might not reflect 2025 trends. Legacy WMS vendors might successfully bundle orchestration, making it invisible rather than an explicit criterion. Or the 5-company threshold might be too high for a single year.

10. At least one major humanoid safety incident will prompt regulatory attention

By end of 2026, at least one humanoid robot incident (injury, property damage, or near-miss with significant public attention) will result in either: (a) a formal regulatory investigation, (b) proposed legislation mentioning humanoid robots specifically, or (c) an OSHA citation or equivalent in a major jurisdiction.

The incidents are already accumulating:

- February 2025: Unitree H1 nearly headbutts festival-goer in China, goes viral

- May 2025: Unitree H1 malfunctions in factory, flails wildly near workers

- September 2025: A lawsuit filed against Tesla and FANUC after a July 2023 incident at the Fremont factory where a FANUC industrial robot arm released during disassembly, throwing technician Peter Hinterdobler to the floor and knocking him unconscious. While this involved a traditional industrial arm, not a humanoid, the $51M lawsuit highlights the scrutiny robot safety is attracting.

- November 2025: Russian AIDOL robot collapses on Moscow stage

As Brooks notes: "never be below any sort of walking robot, no matter how many legs it has, when it is walking up stairs." Bipedal robots are inherently dangerous during balance recovery, they pump in large amounts of energy very quickly when things go wrong.

With companies pushing for production deployments, more robots will operate near humans. The probability of a serious incident requiring regulatory response is high.

Why I might be wrong

Companies might successfully manage safety through conservative deployment (safety barriers, limited public exposure). Incidents might be settled quietly without regulatory attention. Or the regulatory apparatus might simply be too slow to respond within 2026.

11. The robotics community will emphasize standardized benchmarking; major labs will begin competitive comparison

By end of 2026, at least three major robotics labs (from: Google DeepMind, NVIDIA, Physical Intelligence, Figure, OpenAI, Toyota Research, Boston Dynamics, or equivalent) will publicly report results on the same manipulation or navigation benchmark, creating the first serious competitive comparison in robot foundation models.

As I've written elsewhere about LLM benchmarks, they are extremely useful and important to measure progress across model providers. Pushing for more principled evaluation for embodied AI is a tall order, but it would undoubtedly accelerate progress.

However, we also noted that "When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure." Robot benchmarks will face the same Goodhart's Law problems: gaming, overfitting, style over substance. But even flawed benchmarks beat no benchmarks. The field needs some way to compare progress beyond counting YouTube views.

The infrastructure exists: RoboCasa offers 100 tasks with 100K+ trajectories, RoboCasa365 expands to 365 tasks, SIMPLER provides standardized evaluation. Open X-Embodiment demonstrated coordinated data collection is possible. We saw new evaluations like Point-Bench, RefSpatial, RoboSpatial-Pointing, Where2Place, BLINK, CV-Bench, ERQA, EmbSpatial, MindCube, RoboSpatial-VQA, SAT, Cosmos-Reason1, Min Video Pairs, OpenEQA and VSI-Bench gain traction.

The field desperately needs this. Current evaluation is fragmented: everyone reports on their own tasks, objects, and success metrics, promotes a beautifully produced marketing video. You cannot compare π0 to Helix to GR00T N1 because they're evaluated on different things.

Why I might be wrong

Labs might resist standardization because it reveals unflattering comparisons. Physical benchmarks are harder than language benchmarks: who pays for hardware, where does it live, who maintains it? Is simulation accurate enough for evaluation tasks? Coordination might prove too difficult.

12. 3D Gaussian Splatting will become the de-facto standard for spatial representation in robotics

By end of 2026, 3D Gaussian Splatting and derived representations will be among the top 3 most-published topics at major robotics venues (ICRA, IROS, CoRL, RSS) for perception, mapping, or planning.

3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) is a newer way to represent and render real-world scenes that sits somewhere between classic 3D geometry and neural rendering. Instead of reconstructing a mesh or relying on a heavy implicit network, it models a scene as a set of tiny, learnable 3D “blobs” (anisotropic Gaussians) scattered through space. When you render the scene, those Gaussians are projected into the camera and efficiently “splatted” onto the image plane, blending together to produce photorealistic views. The result is increasingly useful for AR/VR, and digital-twin style capture workflows.

In robotics, it's helpful to think of 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) as a modern cousin of traditional SLAM: both aim to estimate camera motion while building a persistent scene representation, but they differ in what they choose to map. Classic visual SLAM pipelines recover poses using geometric constraints (features, epipolar geometry, bundle adjustment) and then store the world as sparse landmarks, dense depth, voxels, or surfels, representations optimized for metric accuracy and downstream planning. 3DGS, by contrast, builds a map made of many small, continuous primitives (Gaussians) whose parameters are optimized so that the scene can be re-rendered to match the images; in that sense it behaves like a dense, differentiable, photometric map.

The interesting connection is that the same signals SLAM already exploits—multi-view consistency, pose refinement, and uncertainty, can be expressed through 3DGS optimization, potentially turning mapping into something that is simultaneously localization-friendly and appearance-complete, bridging the gap between “maps for navigation” and “maps for realism.” More and more teams are trying to bridge this gap, with impressive results. This year we saw papers like SEGS-SLAM, BDGS-SLAM, and dozens of ICCV/CVPR 2025 papers use 3DGS for robot perception and mapping. The advantages compound: real-time rendering, natural integration with semantic feature fields, and representations you can actually inspect and modify.

This is a research trend prediction, not commercial adoption, that will take longer.

Why I might be wrong

The robotics research community might not pivot as quickly as the computer vision community. 3DGS are quite expensive to compute, and while they offer advantages for visual and spatial reasoning, they are not as efficient or effective as SLAM methods. In particular, scale and global alignment are still difficult, so is running it online.

Looking Back to Look Forward

Twelve predictions, most of which I expect (hope?) to be at least partially wrong.

If I had to distill a theme, it's this: 2026 will be the year embodied AI hits the deployment wall. The models are getting good enough. The hardware is almost there. But the gap between a compelling demo and a reliable system that works 10,000 times in a row without human intervention, that gap is wider than the hype suggests.

The VLA paradigm is real and won't reverse. Language grounding, multimodal sensing, and foundation model transfer have fundamentally changed how we build robot brains. But scaling laws, long-horizon reliability, and edge deployment remain open questions. We might see breakthroughs on all three, or we might discover that robotics has different scaling dynamics than language, that the bitter lesson needs a physical-world amendment.

The wildcards are defense spending and safety incidents. Defense investment could reshape the entire field's economics, pulling talent and capital toward applications most researchers would rather not think about. And the first serious humanoid injury will change the regulatory conversation overnight, whether that's warranted or not.

I'll revisit these predictions in January 2027. Some will look prescient; others will look naive. That's the point. Predictions that can't be wrong aren't predictions, they're hedges dressed up as insights.

If you think I'm wrong about any of these, I genuinely want to hear it. The best way to refine a prediction is to have someone poke holes in it. Reach out if you are working on these topics, if you have any evidence either way, or just want to discuss which ones are missing.

No prediction is inevitable, so now it's time to build!

Thanks to everyone who helped me review and provided feedback on this article, in particular Frederic Jacobs.